NEW YORK — As completion of the Dakota Access pipeline remains on standby after the Army Corps of Engineers announced on Sunday that it would not authorize the development company to drill under the Missouri River near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North Dakota, similar projects continue to encroach on indigenous communities across the United States.

“There are probably 20 or so pipelines being protested in various ways at any given time, and they affect many more reservations and traditional homelands than that,” Aaron Carapella, a Cherokee cartographer in Warner, Oklahoma, told MintPress News.

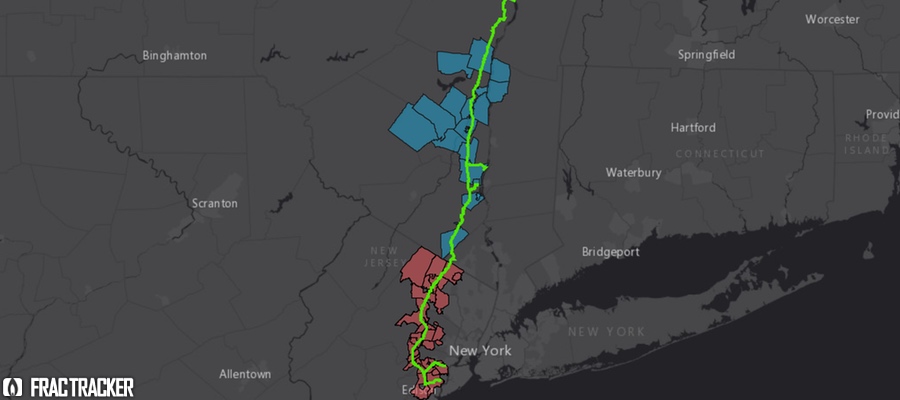

Carapella recently designed a map showing how pipelines under development in the United States cross dozens of indigenous territories, many of which are the sites of contemporary Native communities.

“There are tens of thousands of existing pipelines throughout the land, so I chose to focus on those projects that are not quite completed, that are being resisted, or that are only in proposal stages,” he said.

‘No resistance equals always losing’

Carapella, whose maps illustrate the past and present indigenous presence in the Americas, combined them with new information from various sources.

“I used the government’s own proposed pipelines lists and maps, as well as activist and tribal websites, and overlaid them onto my existing map,” he said.

He added that a task of this nature is difficult to complete.

“I need to include more pipelines on my map, like Comanche Trail and Pecos, both of [which] are being protested,” he said.

“There is one running through a remote part of the Navajo Nation at the Chuska Mountains that is being protested, as well as several across the Great Lakes.”

But he hopes that his project will help to magnify the scale of a continental conflict between Native communities and pipeline projects that, when it breaks into the headlines, is usually framed as a singular issue at a particular location.

“We won some victories, and lost some good causes, but no resistance equals always losing, so resistance is necessary,” he said.

“Campaigns to get out the word are necessary.”

‘Endangering the water of millions’

pipeline In one little-remarked struggle, the Ramapough Lunaape Nation, a small community nestled among the Ramapo Mountains chain of the Appalachians in northern New Jersey and southern New York, face the looming threat of the Pilgrim Pipeline.

“The Pilgrim Pipeline is another of the many needless pipelines running through the Lunaape homeland which is endangering the water of millions, while it appears to be criminally circumventing federal law,” Ramapough Lunaape Chief Dwaine Perry told MintPress.

The Ramapough Lunaape have long been the targets of outside attention, ranging from innocent curiosity to racist invective, due to their traditional life — seemingly paradoxical to some — centered 25 miles from New York City amid the suburbs of New Jersey.

Despite the long record of Lunaape contact with European settlers, dating to Giovanni da Verrazzano’s 1524 voyage into the Hudson River, the Ramapugh Lunaapes’ relative isolation throughout much of colonial and US history lent the group an air of mystery, with their very existence more likely to be mentioned as legend than fact until the 20th century.

“Is this logical, you ask yourself, that here so close to Times Square, several thousand people like these live and have their being?” an irate local historian wrote in 1941.

“No it isn’t logical at all, it’s 150 years and across the world.”

‘They bribed, threatened, even murdered’

Over the ensuing decades, the harsh logic of a surging industrial economy would reach deep into the Ramapough Lunaapes’ mountain enclaves.

Most destructively, Mafia-controlled haulers operating on behalf of the Ford Motor Company’s nearby Mahwah Assembly plant dumped millions of gallons of toxic paint sludge before the facility closed in 1980.

“An analysis of public records and interviews with truckers who hauled Ford’s waste shows mob-controlled contractors dumped anywhere they could get away with it,” an investigative report by NorthJersey.com found in 2009.

“They bribed, threatened, even murdered to maintain control of Ford’s trash.”

Ford’s lucrative contracts sparked clashes between rival mobsters that at times turned deadly.

In a notorious incident that spurred a rare federal investigation of the Mafia’s stranglehold on industrial waste disposal, Genovese crime family figure Joseph “Joey Surprise” Feola “was lured to a garage in 1965 and strangled as a favor to the notorious godfather Carlo Gambino,” NorthJersey.com reported.

“His offense? Stealing the Mahwah stop” — located in the heart of Ramapough Lunaape territory — “from a Gambino-controlled company.”

Watch Hudson River at Risk 6: A Pipeline Runs Through It:

‘Government at all levels’

Despite this momentary attention, the regional news portal also found that “[g]overnment at all levels shares the blame” for Ford’s colluding with the mob and poisoning the Ramapough Lunaape and other communities near the plant.

“For years, it allowed mobsters to turn New Jersey into a toxic dumping ground.”

Toxic Legacy, an investigative series conducted by the Bergen Record in 2005, explored the deadly effects of Ford’s deposits in the old Ringwood Mines landfill site on the surrounding Ramapough Lunaape.

The newspaper’s soil tests found levels of lead, arsenic and xylenes at over 100 times the recommended maximums, while nearby levels of both health disorders, ranging from nosebleeds to cancer, and learning disabilities had skyrocketed.

A lawsuit against Ford by hundreds of Ramapough Lunaape, chronicled in the HBO documentary Mann v. Ford, ended in 2010 with a disappointing settlement.

Their hands forced by the specter of a possible Ford bankruptcy, 633 individual plaintiffs accepted one-time payouts between $4,368 and $34,594 each.

“It’s probably a vacation for a CEO for a week with his family,” lead plaintiff Wayne Mann told NorthJersey.com.

“A healthy family.”

‘The very same watershed’

Steeled by the legacy of Ford, today the Ramapough Lunaape confront the threat of Pilgrim.

A proposed 178-mile, double-barreled pipeline, the project would run from Albany, New York, to Linden, New Jersey, transporting Bakken crude oil south and refined petroleum products north.

“We are adamantly opposed to any pipeline that has no internal market and endangers all of our water, including one of only seven sole source aquifers in the United States,” Perry said.

In July, the Ramapough Lunaape mobilized to Philadelphia, where over 100 helped to lead the March for a Clean Energy Revolution during the Democratic National Convention.

“Pilgrim is proposing to cut through the very same watershed lands where Ford dumped paint sludge into the shafts of the abandoned iron mines once worked by our ancestors,” Perry wrote at the time.

“Learning from our long history of struggle against the toxic effects of environmental injustice, we are now organizing with the broader community to stop Pilgrim’s dirty pipelines before they’re built.”

‘We need help now’

In recent months, the Ramapough Lunaape have joined their struggle with that of the Sioux water protectors at Standing Rock, even offering the Split Rock Sweetwater Camp as a smaller reflection of the massive gatherings blocking the Dakota Access Pipeline half a continent away.

Perry calls it a “site that we have been using for Native American ceremony for over a quarter of a century, and have invited all to enjoy the land and to share in our culture.”

“Currently, the prayers of Split Rock have been directed toward Standing Rock.”

But like Standing Rock, the camp is surrounded by threats.

“Recently the Split Rock Sweetwater Camp has come under a great deal of duress, both from the local Polo Club community, of whom we are the largest landowners, and the Mahwah municipality, in an apparent push to deny us the right to open air prayer and the right to assembly,” Perry said.

He added that opposition has come not only from local police and other public bodies, but also racist vigilantes.

“We have had swastikas and the word ‘hate’ drawn on our sacred home, and an eleven-car police raid on two of the land guardians for charging their phone.”

While the backlash against indigenous self-determination that has included attack dogs, concussion grenades, pepper spray and water cannons in North Dakota takes different forms in New Jersey, it nevertheless seems familiar.

Perry has appealed online for supporters to gather at the site on Friday, when he says it faces the threat of “eviction” by police, days after Mahwah officials warned in a letter that use of the indigenous land as a “place of public assembly” requires zoning approval from the local government.

“In effect Split Rock Sweetwater is now under the same kind of duress as Standing Rock,” Perry told MintPress.

“We need help now, legal and tangible, to help us keep and occupy our own land through this threat.”

‘Resist one pipeline at a time’

As similar struggles develop across the United States, the effects of the unprecedented Native mobilization at Standing Rock and its overwhelming public support remain to be seen.

By all accounts, Dakota Access garnered such massive opposition not because of the development’s exceptionality, but rather its familiarity.

And with a historic, if provisional, victory under its belt, many expect a burgeoning indigenous movement to intensify its resistance to similar projects elsewhere.

“This is an ongoing problem, and we are probably going to have to resist one pipeline at a time for many decades to come, and maybe longer,” Carapella, the cartographer, said.

“This is one victory in a very long battle, a battle that has gone on for 500 years,” he added of the permit denial at Standing Rock.

“We are very aware of the next steps forward.”

Explore Cherokee cartographer Aaron Carapella’s map of pipeline development of tribal lands: