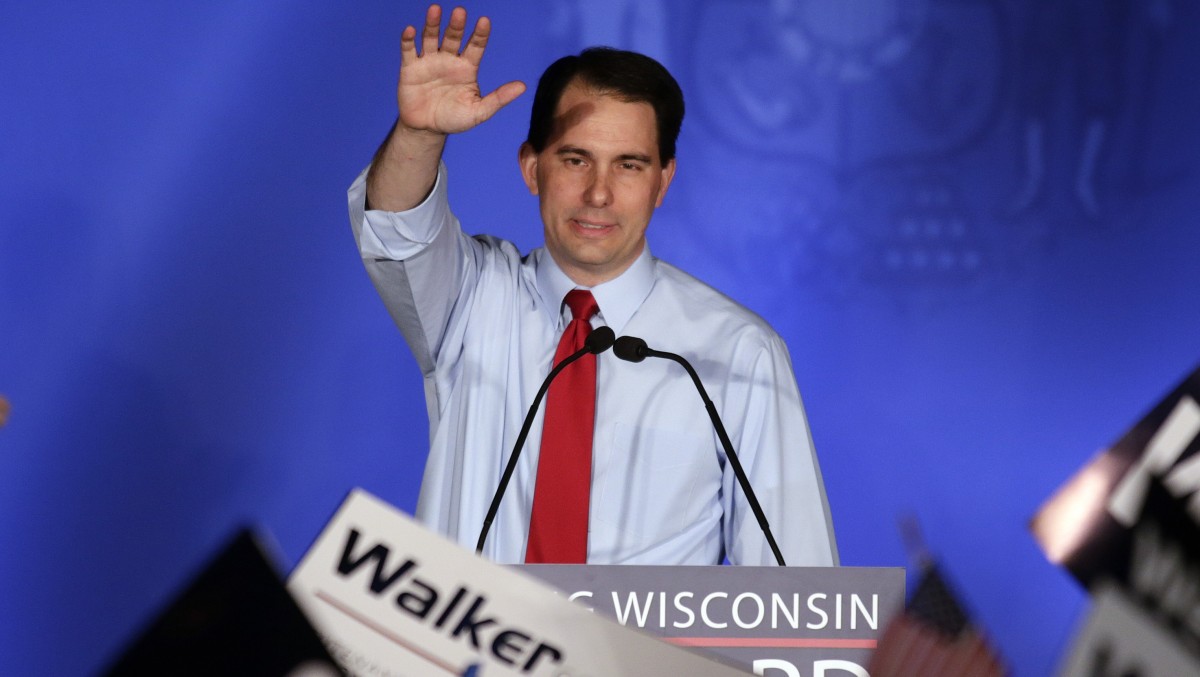

(TEXAS) – The electoral rebuke of efforts to recall Wisconsin governor Scott Walker this past week have been read like tea leaves by all sorts of political commentators. The right, triumphant in seeing a tea party candidate survive the gauntlet, declared that the die was cast for the November election – in the form of a Republican recapture of the White House. The left, licking its wounds, took some comfort in the number of pro-Walker voters who indicated they intended to vote for Obama – the so called Obama Republicans.

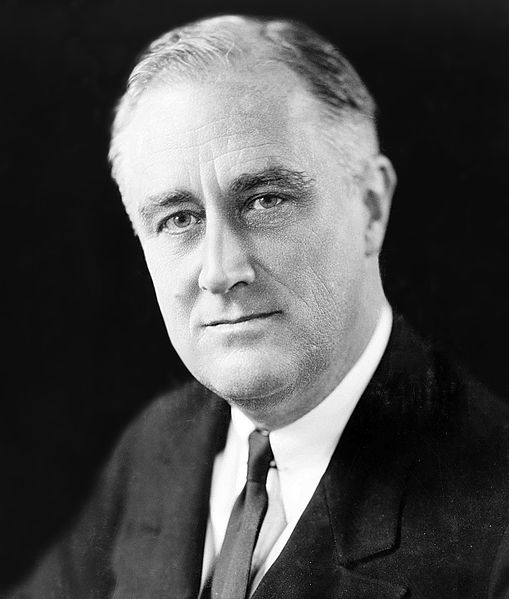

Instead of being a key to the future the survival of Gov. Walker is better understood as a guide to the past. Rather than being a starting point, Walker’s victory marks an endpoint in an era of American labor relations and political economy that began in the 1930s and 1940s. Then, as now, a recent economic collapse had shaken America’s faith in unbridled capitalism while threatening forces abroad darkened our shores and a reformist Democrat had taken office amidst cries of a socialist takeover by the oppositionist Republicans.

Under Roosevelt, who commanded significant majorities in Congress and so could pass much more of his agenda, landmark legislation was passed that created the foundations of the modern American welfare and regulatory state. Also passed, which is often forgotten today, was the Wagner National Labor Relations Act – a key piece of legislation that largely legalized efforts by workers to form unions and engage in collective bargaining while also punishing employer efforts to retaliate against unionizing workers.

This legislation, however, should not be seen as creating the power of American labor. Rather, it should be seen as the capstone of efforts by labor to get a piece of the pie and a place at the economic negotiating table as the country moved forward. In other words, the act did not create American labor as a powerful political force, it recognized it as a new, powerful element in American life that had been growing for decades and which had finally won enough influence to achieve and protect many of its aims.

Achieve them it did. This new era of a politically and economically powerful American labor helped divide the spoils of post-war American growth broadly and deeply; creating, through tenacious negotiations, the occasional strike and legislative muscle flexing, a new society where everyone called themselves middle class even if they worked on a factory line. A prosperous working class masquerading as a middle class bought everything from cars to TV dinners and, in so doing, created a consumers’ republic that has driven American economic growth, for better and for worse, ever since. The new era was epitomized in 1950 by the so-called “Treaty of Detroit” – a five year contract by the United Auto Workers with the big three auto manufacturers that exchanged labor peace for an increased, long-term share of the companies’ revenues.

In hindsight, this golden age of American labor was sustained by several, historically contingent, factors. The first, and most important, was the degree to which American labor was protected by foreign competition. Prior to the Wagner Act, an earlier piece of legislation in the midst of the Great Depression but prior to Roosevelt’s election had destroyed global trade, and thus competition to American labor, in the form of the Smoot-Hawley tariff. The act’s drastic hike in import taxes and retaliation by U.S. trade partners reduced American exports by more than half – temporarily choking off economic growth at home and abroad and deepening the Depression appreciably. While the short-term result created economic misery and political chaos, the long-term result dramatically strengthened the importance and strength of American workers as capital become more reliant on it for both a consumer market and supplier of labor. Political power could not help but flow from that.

Then the war came, and what remained of U.S. economic competitors were largely destroyed, even as the U.S. economy grew stronger. Indeed, the U.S. economy became so strong that it simultaneously fed and equipped its allies in Europe, single-handedly defeated the Japanese in the Pacific and developed the Atomic Bomb – all while rationing at home was increasingly relaxed and kept more for purposes of solidarity with our men overseas than a real need to sacrifice for the war effort. When it was all over, there was no world economy. There was an American economy with various global offshoots that were tied to it in various ways. The U.S. had no competitors and its major economic actors, from companies to labor unions, were effectively monopolies on the global stage. Viewed in this way the 1950s Treaty of Detroit between the Big Three and the UAW can be viewed as a collaborative deal between two global monopolists – American Capital and American Labor – to divvy up the spoils of a victorious war that had destroyed all competition.

This monopoly did not last, though it lasted long enough for several generations of Americans to grow up with the assumption that working-class people were actually middle-class people and that social mobility to bigger paychecks and bigger homes was a foreordained right of being American. By the late 1970s the system began to collapse as first foreign competition, higher oil prices and the inflationary tendencies inherent in a cozy duopoly economy played themselves out. American capital responded nimbly by shifting assets, both physical and financial, abroad and by using their political power to dismantle legal impediments to trade and investment.

American labor, in turn, was not able to adapt, and its problems increased as technology and then immigration replaced more workers with cheaper alternatives. Wages stagnated as the monopoly power American labor had enjoyed for so long due to financial depression and world war evaporated in a competitive market in which the U.S. working class found itself to be the high-cost producer. Now, in 2012, the final parts of the gains labor had made at the height of its economic power and influence – broad and deep employer-paid health insurance coverage of its workforce – is inevitably dying, too, as American businesses find health insurance too expensive to provide.

As goes economic power, so goes political power. Reagan’s busting of air-traffic controllers in the 1980s was the first of many attacks against organized labor by the newly empowered political right. Stagnant wages and falling memberships coupled with a left divided against itself by culture war invective fatally eroded the ability of organized labor to defend itself. They fell back, and as they did so, Democrats became less reliant upon them. Realizing the new impotence of the traditional labor left, so-called New Democrats under Clinton turned to Wall Street and educated, professional and largely middle and upper-middle class voters located in the suburbs for electoral victory. Organized labor was largely forgotten as a spent force that had no alternative to the Democrats anyway. This diminished political role for organized labor could be seen in how easily Centrist Democrats, under Clinton, passed free-trade legislation such as the North American Free-Trade Agreement and Chinese accession to the World Trade Organization.

As goes economic power, so goes political power. Reagan’s busting of air-traffic controllers in the 1980s was the first of many attacks against organized labor by the newly empowered political right. Stagnant wages and falling memberships coupled with a left divided against itself by culture war invective fatally eroded the ability of organized labor to defend itself. They fell back, and as they did so, Democrats became less reliant upon them. Realizing the new impotence of the traditional labor left, so-called New Democrats under Clinton turned to Wall Street and educated, professional and largely middle and upper-middle class voters located in the suburbs for electoral victory. Organized labor was largely forgotten as a spent force that had no alternative to the Democrats anyway. This diminished political role for organized labor could be seen in how easily Centrist Democrats, under Clinton, passed free-trade legislation such as the North American Free-Trade Agreement and Chinese accession to the World Trade Organization.

Then, in 2004, the favored son of the old rust-belt, blue-collar economy of the Midwest – Rep. Dick Gephardt of Missouri – came in a humiliating fourth place in the Iowa Caucuses. Then, in 2008, the new irrelevance of the traditional, blue-collar working class was made even more paramount when Barack Obama defeated Senator Hillary Clinton, who received heavy support from this demographic, in the Democratic nomination contest for president. The rise of anti-union tea party Republicans in 2010 and the survival of Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker in the heart of what remains of union country is subsequent history.

American labor and the unions that represented them rose up on the backs of a global American economic monopoly. They are falling back to the position they found themselves in prior to the 1930s, as that monopoly has collapsed. If American labor and the broader political left are to survive this new era of globalization they will have to confront the economic reality of foreign competition and technological change in a new era when labor is commoditized not just nationally, but globally. How they can do that, beyond engaging in the self-defeating rage of protest politics, remains to be seen.