Operation Warp Speed has grabbed all the headlines when it comes to the federal government’s efforts to deploy a COVID-19 vaccine when it becomes available. A colossal enterprise, some supply chain experts have called it “an Amazon Prime delivery model for a vaccine.”

But, the real distribution networks tasked with the job are located in 64 jurisdictions brought together under the Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Prevention and Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases (ELC) cooperative agreement; a 25-year old funding program inside the CDC used to enhance “state, local and territorial capacities for emerging infectious disease control.”

In March, the Trump Administration secured $631 Million from Congress for these jurisdictions through the CARES Act to “expand their capacity for testing, contact tracing, and containment,” according to HHS director, Alex Azar. But, the CDC has come back, months later, with a counteroffer ten times the original award, requesting $6 Billion to cover the logistical requirements of distributing a vaccine to the entire U.S. population and beyond.

The $6 Billion-dollar request was made privately among CDC officials and members of Congress before CDC director Dr. Robert Redfield called the agency’s need for more funds “urgent” during an open congressional hearing last week. The decision to go public was likely motivated by the Democrats’ blocking of the GOP coronavirus relief bill last week, which contained the $6 Billion allocation in addition to the $20 Billion requested separately by HHS for further vaccine manufacturing and development, The Hill reported.

First blood in November

Besides the 50 states, ELC jurisdictions also include five U.S. territories and three freely associated states, as well as all federally recognized tribal nations serving more than 50,000 people. In Trump’s first year in office, the CDC introduced a new funding mechanism for the jurisdictions to more quickly deploy resources in a public health emergency over which the CDC, itself, exercises discretion.

In August of 2019, the ELC launched “a new 5-year period of performance” dubbed the “next generation” ELC Cooperative Agreement that prioritized surveillance, detection, and response to “the growing threats posed by infectious diseases,” a full two months before news of a mysterious bat-borne virus broke. Other priorities included implementing “public health interventions and tools,” which together with their stated intent to use “surveillance data to inform and prepare intervention strategies,” sounds exactly like contact tracing.

The $631 Million from the CARES Act went directly to these ends in all jurisdictions and now, as a still-unknown COVID-19 vaccine comes closer to fruition, the real and expensive implications of a mass vaccine distribution operation in a country of 328 million people begin to take shape.

The sheer scope of the proposed mass inoculation entails a herculean logistical effort to supply millions of vaccine doses to all the hospitals, clinics, and assorted facilities that will physically deliver them to the citizenry. It is also a considerable political undertaking, which Redfield himself took on by sending a letter to all state governors urging them to waive requirements and expedite applications for distribution centers in order to have them fully operational two days before the presidential election.

The November 1 deadline came down straight from the Trump White House, according to Redfield, who stressed that the president wanted them “to do everything in their power to eliminate hurdles for vaccine distribution sites to be fully operational” by that date.

A protracted affair

Marcus Plescia from the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASHTO), worries that lack of funding will leave many health departments in the “technological dark ages” because they “will struggle to adequately track who has been vaccinated and when.” Plescia also believes that underfunded vaccine distribution efforts will pose a public health challenge, claiming that it would “probably going to be even worse than the problems with testing.”

In an August 4 memo circulated among members of Operation Warp Speed, the CDC delineated many of these challenges and identified five jurisdictions that would serve as “pilot sites for joint planning missions” for the eventual distribution of the COVID-19 vaccine. North Dakota, Florida, California, Minnesota, and Philadelphia are working to “plan and prepare for the COVID-19 vaccination response” helping to create a “planning tool with model approaches,” that will then be used in the remaining jurisdictions.

Even after vaccinations get underway, life won’t return to normal for a while, according to a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, who told KHN in August that “We have to be prepared to deal with this virus in the absence of significant vaccine-induced immunity for a period of maybe a year or longer,” due to the limited doses expected to be available in the fall.

The CDC’s memo revealed that the National Academies of Science has formed a committee to determine which “populations [are] to be reached early,” formulating the criteria that will be furnished to lawmakers, in order “to ensure the equitable allocation of limited doses until there is sufficient global supply.”

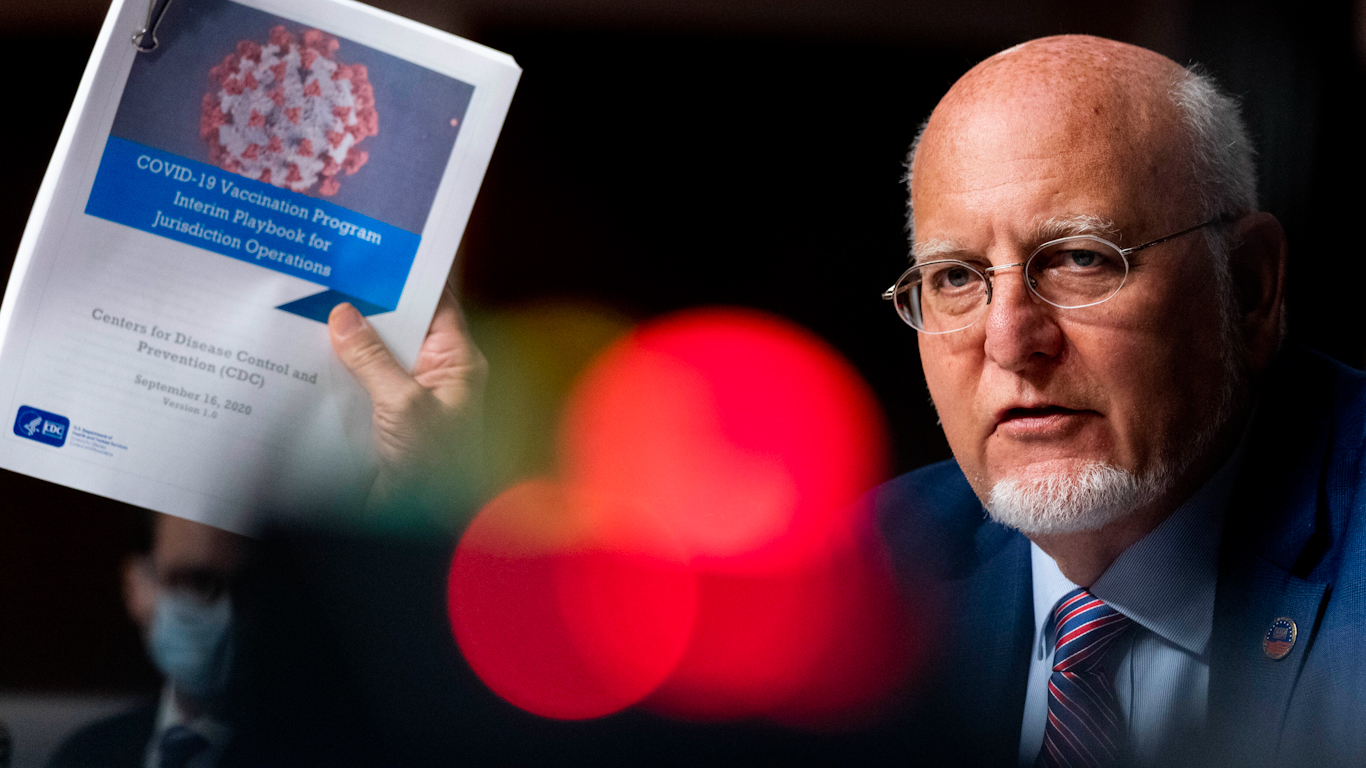

Feature photo | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Robert Redfield holds up a CDC document that reads “COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook for Jurisdiction Operations” as he speaks appears at a Senate Appropriations subcommittee hearing on a “Review of Coronavirus Response Efforts” on Capitol Hill, Sept. 16, 2020, in Washington. Andrew Harnik | AP

Raul Diego is a MintPress News Staff Writer, independent photojournalist, researcher, writer and documentary filmmaker.