NEW YORK – Graphika is the toast of the town. The private social-media and tech-intelligence agency that tracks down bots and exposes foreign influence operations online is constantly quoted, referenced and profiled in the nation’s most important outlets. For example, in 2020, The New York Times published a fawning profile of the company’s head of investigations, Ben Nimmo. “He Combs the Web for Russian Bots. That Makes Him a Target,” ran its headline, the article presenting him as a crusader risking his life to keep our internet safe and free. Last year, business magazine Fast Company labeled Graphika as among the 10 most innovative companies in the world.

There is no doubt that Graphika leans into this cool and dynamic corporate image. From its beginnings in 2013, the company has expanded to employ dozens of people at its trendy Manhattan office. Describing themselves as “cartographers of the internet age,” the company puts out investigation after investigation about foreign influence operations online, especially concentrating on Russian, Chinese or Iranian attempts to manipulate social media. A layperson could certainly be blinded by its science and impressed by the complex and innovative graphs and charts. Yet when it comes to similar but far larger U.S. government programs, the intelligence and analysis agency is silent.

The magnets around Graphika’s compass

One reason for this could be that Graphika is directly funded and staffed by those same American organizations. The New York-based company is not particularly transparent about its sources of income; however, on its website, it lists the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Minerva Initiative – a research program under the Department of Defense – as its chief “partners” in funding. Government records show it also sought and received $3 million in grants from the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force over the previous two fiscal years.

In addition to this, Graphika has partnered with a number of organizations, including the Atlantic Council, a NATO-offshoot think tank funded by the arms industry and the U.S. government. The Atlantic Council has been at the forefront of both vigorously wiping pages and accounts critical of the U.S. government and spreading lurid accusations about the power of Russia to influence foreign elections and media. Graphika and the Atlantic Council have joined forces on a number of different projects, including a 2019 joint report, on social media bots. The two organizations are also a part of the Election Integrity Partnership, a group that purports to protect the American political system from fake news. Another member of that group (and a listed partner of Graphika on its website) is the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO), an organization perhaps most famous for its work in convincing Twitter to delete accounts for the crime of “undermining faith in the NATO alliance.” The SIO is led by Alex Stamos, who is on the board of NATO’s Collective Cybersecurity Center of Excellence. In addition, Graphika lists among its partners The Syria Campaign, an organization dedicated to drumming up support and funding for the controversial group the White Helmets.

And inside its compass

If this is the chief organization trusted to keep us safe from bad-faith state actors, there is already a significant problem. Perhaps most worryingly from an internet freedom angle, however, is the fact that Graphika is staffed in large part by former intelligence agents from the alphabet soup of three-letter agencies in Washington.

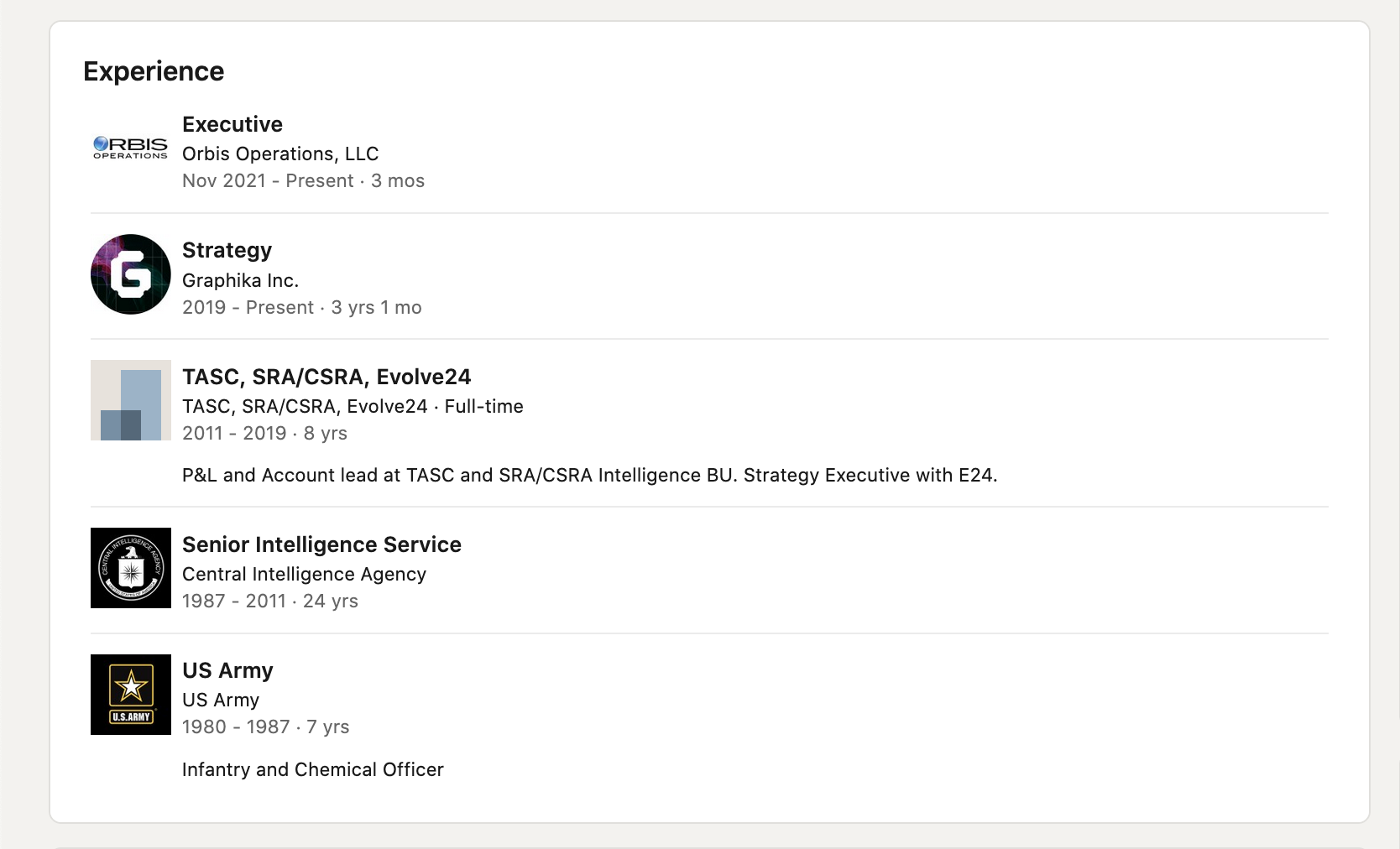

Chief among these is strategy executive Chris Bane. Prior to joining Graphika, Bane spent 24 years in the CIA and seven in the U.S. Army, where he became an infantry and chemical officer. Another former spook is the director of federal programs, JoAnn Perry, who served for three and a half years at the CIA as an intelligence analyst advising policymakers on Middle Eastern affairs. Meanwhile, Lauren Pencek, the company’s vice president of finance and operations, worked at the NSA, eventually rising to become the agency’s director of corporate strategy. Before her time at the NSA, she worked for four years at arms manufacturer Northrop Grumman.

Pencek’s career history underlines the connections between the national security state, the weapons industry, and the emerging tech world. She is far from the only Graphika employee with a similar background. Director of investigations Tyler Williams, for example, spent nearly two years at BAE Systems and nearly seven at Booz Allen Hamilton before joining Graphika. At BAE Systems, he is said to have managed a portfolio of over $75 million for programs totaling more than $500 million. In another job at government contractor ANSER, Williams worked hand-in-hand with the Department of Homeland Security.

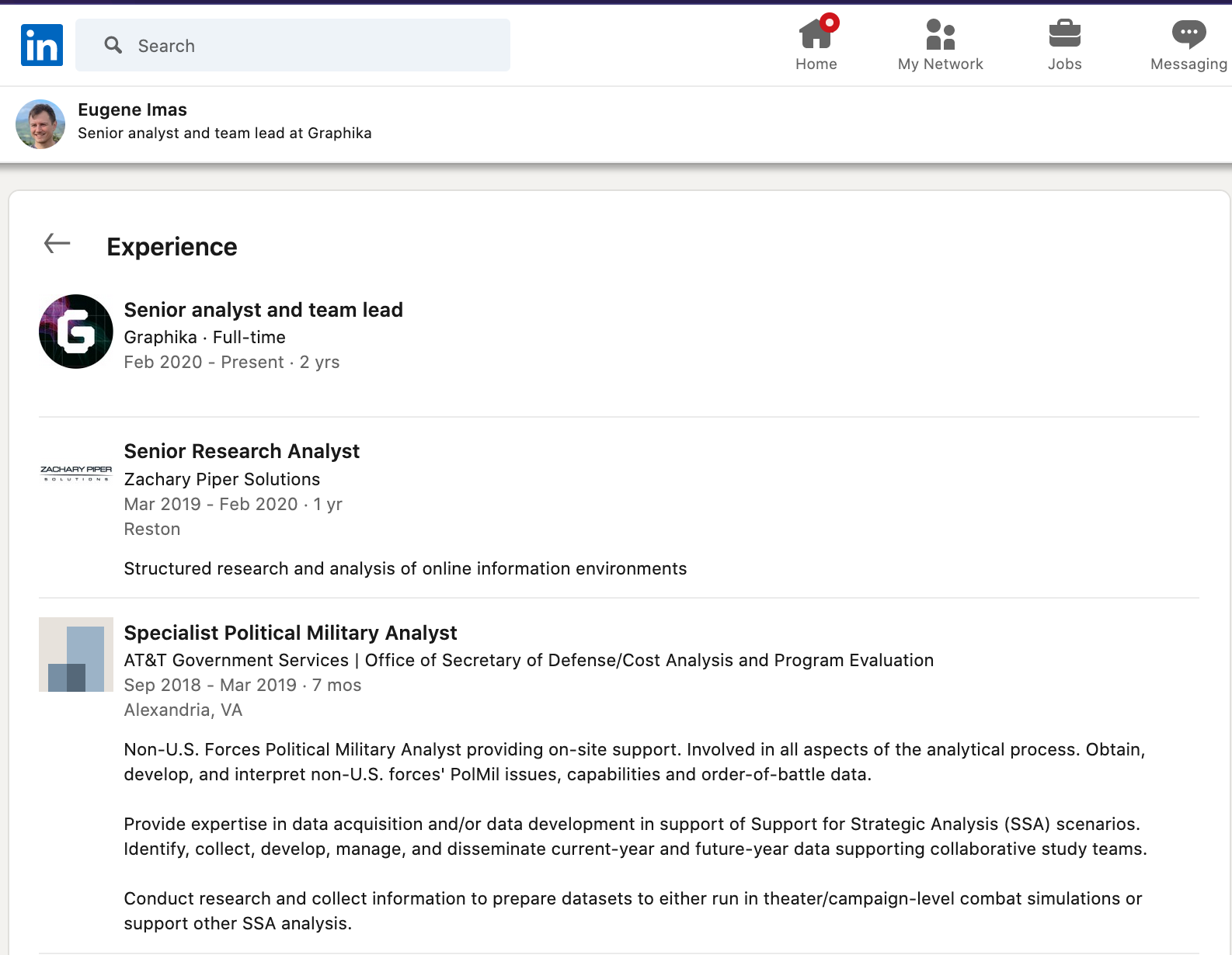

Eugene Imas, Graphika’s senior analyst and team lead, has also taken a very “spooky” career path. Studying Russian at Georgetown University (a school widely known as something akin to “CIA U”), Imas went on to work as a political and military analyst contractor for the Office of Secretary of Defense, where he provided intelligence for American war simulations against Russia. Meanwhile, Jennifer Mathieu spent more than 16 years in senior positions at defense contractor MITRE before switching to Graphika in August to become its chief technology/product officer.

Even Graphika’s staff with journalistic backgrounds have eyebrow-raising connections. Chris Hernon, who contributed to Graphika’s report on Russian influence operations, was a member of the U.K. government Institute for Statecraft’s Integrity Initiative, a secret group of hawkish journalists that the British intelligence establishment has used to plant false and coordinated stories into media around the world.

Connecting the worlds of the national security state, the defense industry, and social media is the aforementioned Ben Nimmo. In addition to his role at Graphika, Nimmo is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and was NATO’s press officer between 2011 and 2014. Last February, he was also appointed as intelligence chief for Facebook and Instagram parent company Meta. The coldest of cold warriors, Nimmo has accused everybody from Welsh pensioners to internationally-recognized Ukrainian pianists of being Russian bot accounts. Unfortunately, in his positions at the Atlantic Council and Meta, he is in a position to take action on his suspicions, allowing the botfinder general to act as prosecutor, judge and executioner.

Facebook Hires NATO Press Officer Ben Nimmo as Intelligence Chief

The English Connection

An inordinate number of Graphika employees have been educated at the Department of War Studies at King’s College London – a notorious, intelligence-linked institution that MintPress News has profiled in depth. The Department of War Studies is the training ground for a huge number of NATO spies and, worryingly, journalists now working in politically sensitive areas such as Russia or the Middle East – a connection that suggests collusion between the national security state and the fourth estate.

A 2009 study published by the CIA extolled the virtues of sending its agents to King’s College London for advanced training from academics with “extensive and well-rounded intelligence experience.” “Exposure to an academic environment, such as the Department of War Studies at King’s College London, can add several elements that may be harder to provide within the government system,” it concluded. In 2013, former CIA Director and then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta gave a speech at the department, where he waxed lyrical about its importance to the agency and to the intelligence community more generally. “I deeply appreciate the work that you do to train and to educate our future national security leaders, many of whom are in this audience,” he said.

A School for Spooks: The London University Department Churning Out NATO Spies

Graphika’s director of analysis, Melanie Smith, is one of many company employees who studied at the same foreign university department. Smith graduated with a master’s degree in Geopolitics, Terror and Security, a course that King’s College London itself makes clear is largely for military officers or spies. Since 2015, she has also been employed by the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, a think tank funded by the arms industry and by a myriad of Western governments (including the United States).

Chair of the Advisory Board and Chief Innovation Officer Camille François is also a War Studies alumnus. A former special adviser to the Office of the French Prime Minister, she has also worked closely with DARPA in the United States and was selected in 2014 to train in “cyber operations” at the NATO School in Oberammergau, Germany. Her studies at Columbia University were paid for by the State Department and the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Years later, she re-entered academia to attend the Department of War Studies, where, in 2019, she produced a report on the so-called Russian troll farm, the Internet Research Agency.

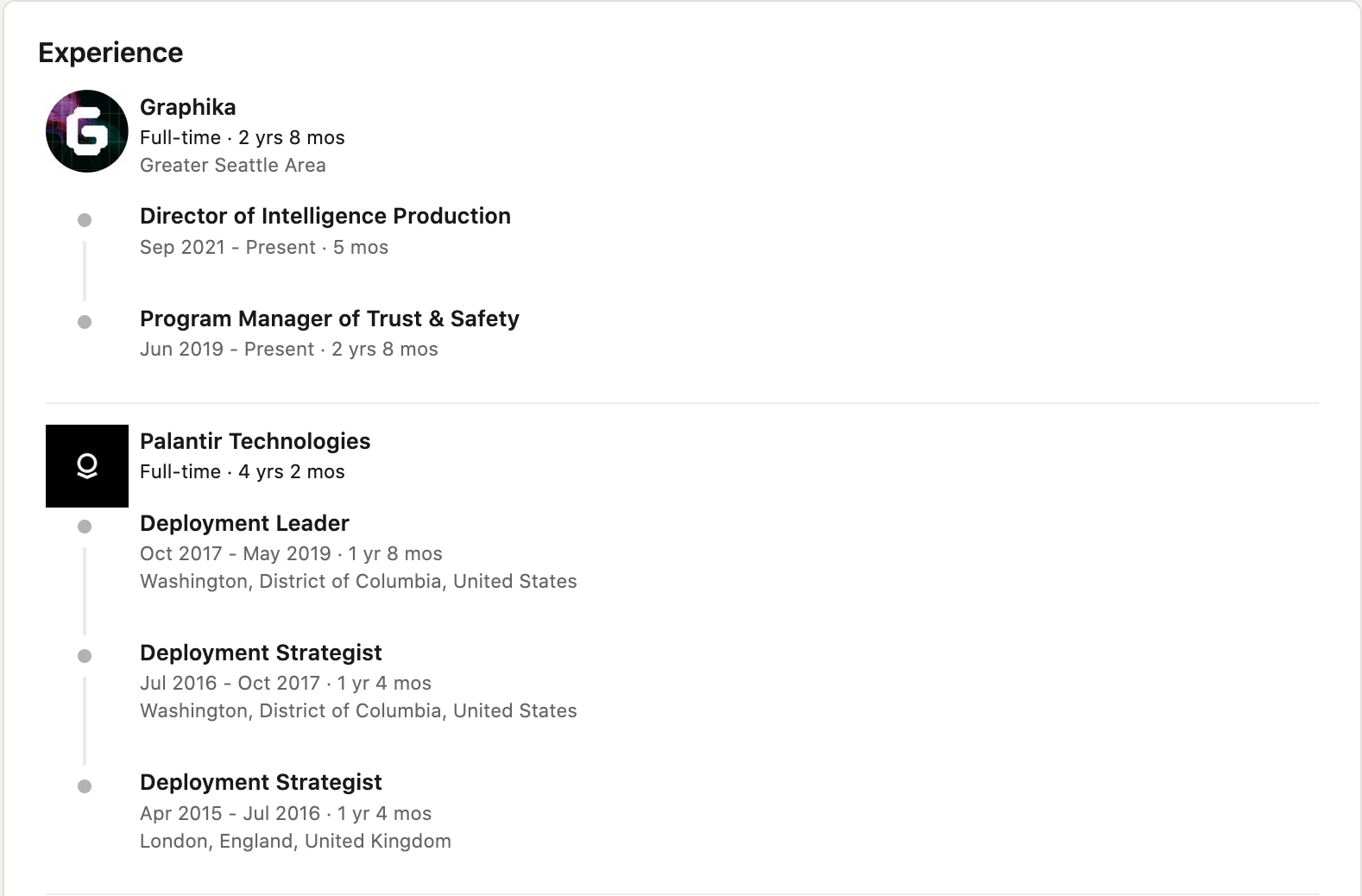

After five years in the U.S. military, Joseph Carter completed a master’s at the Department of War Studies. He later worked for Palantir and joined Graphika in 2019, becoming the company’s director of intelligence production.

Certainly, the number of key Graphika individuals with deep connections to the national security state raises questions about the independence and neutrality of such an organization. Indeed, if there were any remaining doubts that the company functions as a front for the U.S. deep state, then its senior intelligence analyst Denitsa Nikolova removes them. Describing her job at Graphika on her professional LinkedIn profile, Nikolova writes (emphasis added):

Denitsa uses analytical methods and tools to study complex online networks in an effort to provide situational awareness to U.S. government clients. Denitsa specializes in surveying the online political environments of various countries in an effort to protect U.S. interests from coordinated and inauthentic online activity.

The description makes crystal clear that the organization exists to protect or promote not the public’s interests, but Washington’s. Prior to Graphika, Nikolova worked for the U.S. Mission to NATO in Brussels and with former King’s College London War Studies Professor Thomas Rid on his book about Russian disinformation campaigns. Another Russia hawk, Rid was crucial in mainstreaming the increasingly gauche theory that Russia “hacked” the 2016 election, even testifying before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on the “dark art” of Russian meddling and condemning WikiLeaks and alternative media journalists as unwitting agents of disinformation.

The Notorious London Spy School Churning Out Many of the World’s Top Journalists

The best defense… (is a good offense): the takedown of Corbyn

For all the talk of foreign interference in domestic politics, Graphika has weaponized its reporting in attempts to change public discourse around the world. In 2019, the anti-imperialist, pacifistic, NATO-skeptical Jeremy Corbyn was on the verge of becoming prime minister of the United Kingdom. Corbyn – who wanted to ditch nuclear weapons, radically raise taxes on the wealthy, pursue a path of dialogue with other nations, and establish a system of 21st-century socialism at home – represented a mortal threat to establishment interests.

With the help of the Integrity Initiative, there was a coordinated government-intelligence-media effort to destroy Corbyn, with claims that he was a secret Russian spy. The Atlantic Council described him as “the Kremlin’s Trojan horse.” Secretary of State Mike Pompeo revealed that the U.S. was trying its “level best” to prevent a Corbyn victory. Meanwhile, a British Army general warned that if Corbyn’s Labour Party won the election, the military would stage a coup.

But Corbyn’s team had an ace up their sleeve. Just days before the election, it released 451 pages of documents of negotiations between Conservative government members and American corporations, showing that the Tories were in negotiations to sell off Britain’s National Health Service (NHS) to foreign interests. The revelation threatened to sink Boris Johnson.

Thankfully for Johnson, Graphika sprang into action, with Nimmo immediately announcing that the documents “closely resemble…a known Russian operation.” Within days, Graphika produced a long report insinuating that Corbyn was – wittingly or not – part of a Kremlin campaign.

At no point did anyone challenge the veracity of Corbyn’s documents. Nimmo and Graphika’s words, however, allowed the media to spin the story against Corbyn, so the national narrative shifted from “Tories selling off our precious NHS” to “Corbyn working with Russians to push propaganda,” thereby helping to torpedo the latter’s October Surprise and ensure years more of Conservative rule. In the cold light of 2022, the Johnson administration is indeed carrying out its plan to privatize the country’s healthcare system.

More recently, Graphika has also charged Iran with attempting to interfere in Scottish politics, especially on the question of independence, claiming the Islamic Republic was creating networks of inauthentic bots to push for a breakup of the United Kingdom. A further report alleged that a powerful Iranian influence operation was blaming the United States for its response to COVID-19 while praising China’s reaction, all the while pumping out pro-Iran and pro-Palestine propaganda.

Propaganda about propaganda

The Manhattan-based tech firm has been at the forefront of the establishment attack on alternative media, attempting to construct a non-existent link between left-wing sites, the Kremlin, and the Trump reelection campaign. In 2020, Nimmo and François wrote a report insinuating that a Russian government operation had infiltrated a host of well-known independent news sites, including MintPress, The GrayZone, InTheseTimes, and Common Dreams. The crux of the Graphika report claimed that a microblog called “Peace Data” was attempting to build an audience by “partner[ing]” with them and reposting their content. MintPress publishes under a Creative Commons license, meaning anyone can freely rehost content it produces, and there are a myriad of websites and microblogs that do just that. At the time, nobody at MintPress was even aware of Peace Data’s existence.

In its report, Graphika described MintPress as “a U.S.-based site with a focus on the Middle East that has described U.S. foreign policy as ‘an imperialist agenda that believes it’s possible for America to bomb its way out of every difficult situation.’” While there may be an element of truth to that description, from the context, it is clear that this is intended to scandalize the reader.

Without evidence, Graphika claimed that Peace Data was a Kremlin-controlled operation, noting that a sure giveaway was its “anti-Western tone” that “accused Western countries, the E.U. or NATO of imperialism or interference in other states,” its stance against the Saudi-led bombing of Yemen, and sympathy for the plight of Palestinians or Kashmiris. The implication of this, as The GrayZone’s Ben Norton noted, was clear: “If journalists acknowledge U.S. imperialism exists, report critically on Western foreign policy, or show sympathy toward Yemen, Palestine, and Kashmir, they are aiding and abetting the Kremlin.”

The vast majority of Peace Data’s content was in Arabic, not English, and only 5% of its articles related to the 2020 U.S. elections at all, strongly indicating that this was not a Kremlin interference operation to get Trump elected. Furthermore, its reach was utterly minuscule, as even Graphika was forced to concede. A measure of this is the fact that its English-language Facebook page had only 198 Likes by the time it was closed down. If this was indeed an influence operation, it was incompetent and ineffectual, and certainly not worthy of so much attention from a hotshot New York intelligence firm. An individual could have reached a larger audience by talking loudly in a busy movie theater.

The attempts to link Peace Data to well known anti-war sites were also extremely weak. As Miles Kampf-Lassin, web editor at In These Times, noted on Twitter: “[T]he entirety of this attempt to ‘infiltrate and exploit’ In These Times by Russian trolls consists of a single email sent from a random address to our general submission email that was never responded to. Just so everyone is clear on what’s actually going on here.”

Umm, the entirety of this attempt to “infiltrate and exploit” @inthesetimesmag by Russian trolls consists of a single email sent from a random address to our general submission email that was never responded to. Just so everyone is clear on what’s actually going on here. https://t.co/sMPcgCMY9S

— Miles Kampf-Lassin (@MilesKLassin) September 11, 2020

Despite the gaping holes in its methodology, the report caused a media storm. The New York Times published a series of long articles wherein it interviewed two of the only people to have written original content for Peace Data. Strangely, if this was truly a Russian influence operation, both men were Russia hawks affiliated with the right-wing of the Democratic Party. One had even worked for conservative Democratic Congressman Don Beyer.

The suspicions that this was actually an American guilt-by-association operation were increased after Peace Data released a response in laughably poor English – a statement that read far more like an American impersonating a Russian speaking English than a genuine Russian. There were no such glaring grammatical errors on Peace Data’s website, let alone in every sentence. Nevertheless, media around the world took the poor English to be a sure sign of a Russian influence operation, despite the fact that real Russian-backed outlets like Sputnik or RT do not make such errors.

A dissent-snuffing template?

The Graphika report is eerily similar to a 2016 investigation by a shadowy group calling itself ‘PropOrNot.” In the wake of the 2016 election shock, PropOrNot claimed to have used sophisticated “internet analytics tools” that had identified over 200 fake news websites that were “routine peddlers of Russian propaganda” – the implication being that they helped Trump win the election. Included on the list were WikiLeaks and Trump-supporting right-wing websites like The Drudge Report; anti-Trump websites that were also critical of Hillary Clinton, like MintPress News, Truthout and The Black Agenda Report; as well as libertarian vehicles like Antiwar.com and The Ron Paul Institute. In other words, any news source that was critical of the establishment.

A sure sign that you are reading Russian propaganda, PropOrNot claimed, was if the source criticizes Obama, Clinton, NATO, the “mainstream media,” or expresses reluctance to go to war with Russia. As PropOrNot explained, “Russian propaganda never suggests [conflict with Russia] would just result in a Cold War 2 and Russia’s eventual peaceful defeat, like the last time.”

Despite refusing to show any methodology or even reveal who they were, PropOrNot’s claims caused a months-long media meltdown, and swiftly led organizations like Facebook, Google, YouTube and Twitter to radically alter their algorithms to promote “authoritative sources” and demote “borderline content.” The result was immediate. Overnight, alternative media and anti-establishment voices lost their audience. MintPress lost nearly 90% of its Google search traffic; AlterNet experienced a 63% reduction; Democracy Now! 36% and Truthout 25%.

As writer Caitlin Johnstone noted, censorship by algorithm does far more damage than conventional censorship, as it is far less noticeable. Ultimately, the PropOrNot saga allowed the establishment to tighten its grip on the means of communication and effectively shut out dissenting voices.

It is now almost certain that PropOrNot was not a neutral, independent organization, but the creation of Michael D. Weiss, a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council. A scan of PropOrNot’s website showed that it was controlled by The Interpreter, a magazine where Weiss is editor-in-chief. Furthermore, one investigator found hundreds of examples of the Twitter accounts of PropOrNot and Weiss using the identical and very unusual turn of phrase, strongly suggesting they were one and the same. Today, Weiss is a senior fellow at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue, alongside Graphika’s director of analysis, Melanie Smith.

The power of faux-neutrality

Even a cursory look at Graphika’s funding sources, the background of its staff, and its output should be enough to raise alarm bells about its motives and purpose. Graphika is funded by the U.S. national security state, staffed by “former” agents, and produces content that greatly furthers the national security state’s agenda. “If it looks like a duck, walks like a duck and quacks like a duck,” so they say.

These semi-state actors play a very important role in today’s online landscape. In the 1970s, Graphika employees would likely be working for the CIA, producing internal reports for the U.S. government. The trick in the 21st century is to farm out this work to “private” companies funded in large part by the government and staffed with former agents, all the while presenting their findings as neutral, reliable and factual.

If this were the CIA or the NSA controlling social media and deleting hundreds of thousands of Chinese, Iranian or Russian accounts or suppressing domestic alternative media, there would be far more public pushback. Yet this gossamer-thin veil of neutrality from “independent” organizations has allowed a situation where the foxes have taken charge of the henhouse of online communications, promising to keep us safe from ineffective Russian operations, all the while bombarding us with propaganda that is helping drive us to the precipice of war.

Feature photo | Graphika founder and CEO John Kelly testifies before the Senate with other leaders in the private intellegence community. Photo | AP | MPN

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.