SACRAMENTO — Voters will go to the polls today in California, a state with an unusual and controversial primary system that many election analysts are calling a failure.

The June 7 primary, like every California primary since a 2010 ballot initiative reformed the state’s electoral system, is a “nonpartisan blanket primary,” also known as a “top two primary” or a “jungle primary.”

Jonathan Bernstein, a political scientist who writes for Bloomberg View, called the system “California’s election calamity” in a June 3 editorial, adding:

“California voters are set to vote in their primary on Tuesday, and will suffer the consequences of a serious self-imposed mistake in how they run their state. No, it has nothing to do with the presidential race. The disaster is its ‘top two’ system, in which the candidates for state offices — regardless of party — go on to compete in the general election in November if they finish first and second in the primaries.”

Under the system, voters can write-in the name of any candidate they want in June, but write-in candidates are forbidden at the November general election.

“[I]f the polls hold up, two traditional Democrats will survive the first round and face off in November,” Bernstein forecast. The heated race between Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton for the Democratic presidential nomination will result in far more Democratic-leaning voters hitting the polls than Republicans, he suggested.

Turn out for June primaries has been extremely poor since 2010, in part because ballot initiatives themselves were moved from interim elections to the November general election at the same time as the adoption of the jungle primary.

“Unsurprisingly, it turned out that Californians were eager to go to the polls to vote for initiatives, but not so eager when there was nothing more interesting at stake than a primary battle for the state legislature,” wrote Kevin Drum in a Mother Jones analysis of the system last year.

An initiative that could legalize marijuana possession and use for adults in the state is likely to drive voters to the polls in November.

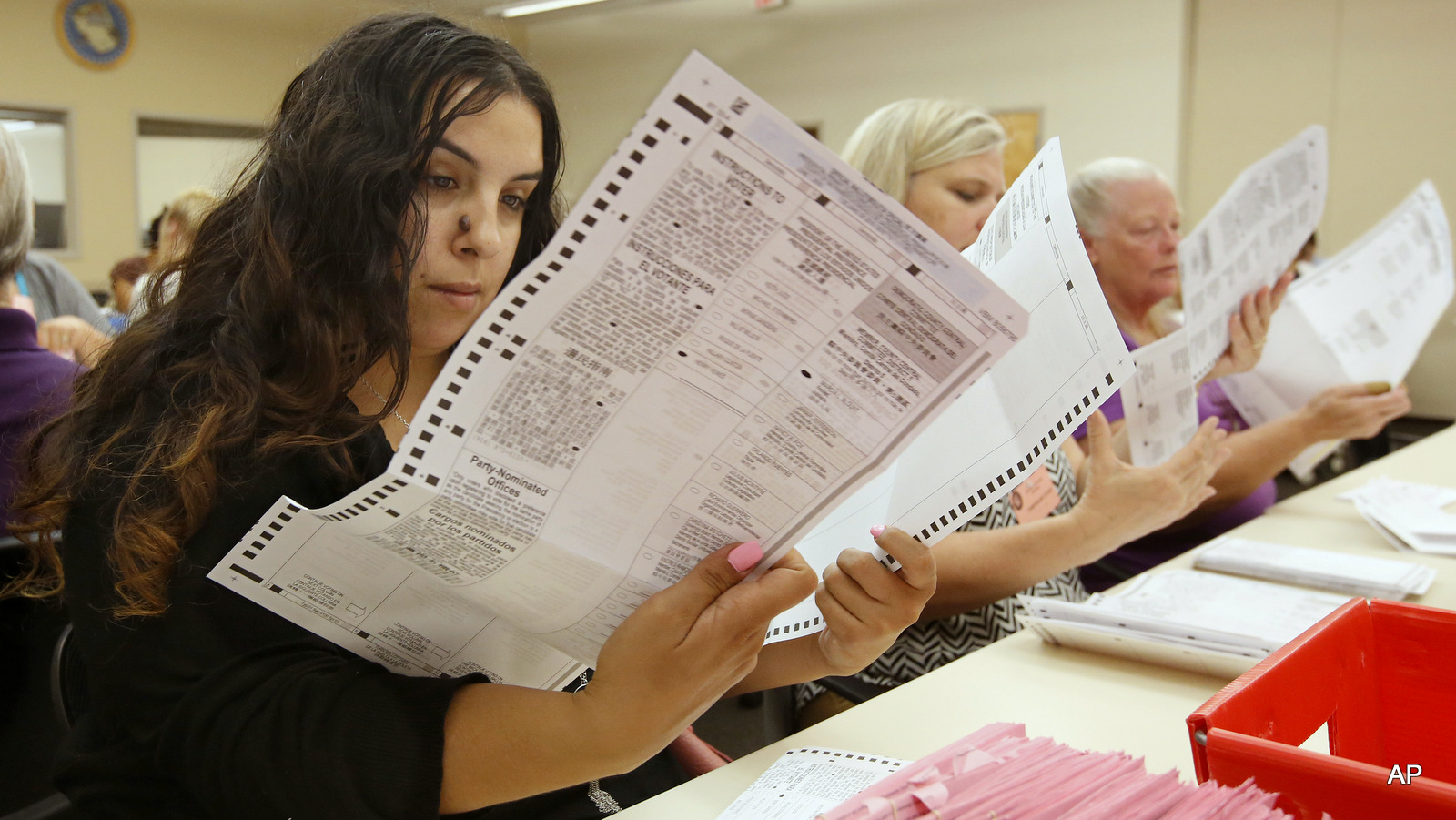

The primary ballots also present a confusing picture to voters, Drum suggested:

“[M]ost voters knew virtually nothing about any of the candidates. Were they moderate? Liberal? Wild-eyed lefties? Meh. Voters weren’t paying enough attention to know.”

On this year’s ballot, for example, California voters will select from 34 candidates for a single open seat in the U.S. Senate. Each candidate is designated only by his or her name, political party, if any, and in some cases, a basic job title.

Although intended to encourage the election of more “moderate” candidates, in the hopes of ending bipartisan conflict in the California Legislature and other voter-elected state off, there’s little sign that it’s had the intended effect. “[E]arly evidence doesn’t suggest that a top-two primary makes much difference,” Drum suggested after examining a series of academic studies into the jungle primary.

Harry Enten, a senior political analyst for FiveThirtyEight, a site specializing in statistical analysis, concurred in 2014:

“That’s not to say California’s top-two system won’t eventually have a moderating effect (although Washington state, which has had a top-two system since 2008, hasn’t seen a move to the middle). We’ll have to wait for a few more election cycles to be more confident one way or the other. But right now, a top-two primary doesn’t seem to alleviate polarization.”

In a 2014 blog post, Cindy Sheehan, an anti-war activist and a Peace & Freedom Party candidate for governor of California, suggested the system fatally hampers third parties’ movement-building efforts:

“‘Cindy, I can’t wait to vote for you in November.’

‘Sigh,’ these are nine words I have heard much more than once since I came in 7th when I competed for Governor in June in California’s Top Two, or Jungle, Primary.”

Sheehan came in the 7th in the primary, ending her campaign and rendering her supporters unable to vote for her in November. She continued:

“My campaign felt that one of our biggest obstacles was to overcome the apparent lack of understanding of this anti-democratic law (that every political party in California opposed in 2010, even the Democrats and Republicans) that the voters themselves passed because, even though we have the ability to get initiatives on the ballot here in California, more often than not, those initiatives favor the 1% and the voters here consistently vote against their own interests being easily influenced by expensive, yet effective, mass-marketing techniques.”

In a 2014 op-ed in the Los Angeles Times, Harold Meyerson called for the system to be abolished, noting the polarized and inhumane nature of the state’s politics:

“To date, few if any tea party Republicans have been dislodged. A number of self-professed moderate Democrats do hold seats in the Legislature, but that’s been the case since roughly 2002, when the state’s leading energy and banking interests realized the days of Republican rule were over and began to back candidates in Democratic primaries. Recently, some of these moderates abstained on a bill that would raise the state’s minimum wage — a dubious achievement for legislators who disproportionately represent the state’s poorest districts.”

“That’s the book on the jungle primary,” he concluded. “It’s time for state voters to scrap it.”