On Thursday, December 4, 1969, at about 4:30 AM, three unmarked Chicago police cars and a panel truck left the 26th Street office of the Cook County state’s attorney and headed west. The lakefront air was bitterly cold, and the vehicles moved deliberately past the empty lots, gutted warehouses, and walk-ups that dotted the city’s west side like rows of rotting teeth.

Ten minutes later they’d arrived at their destination: an old yellow brick two-flat at 2337 W. Monroe. Parking 50 yards up the street, 14 officers tumbled out, clad in leather jackets and fur hats. Their armaments included one .357-caliber pistol, 19 .38-caliber pistols, one carbine, five shotguns, and one Thompson submachine gun with 110 rounds of ammunition.

They had no tear-gas canisters, no sound equipment, and no spotlights; none were necessary.

They split up, forming three groups. Five officers ambled up the six stone stairs at the front of the two-flat and entered through the narrow outer hallway, while six moved through the passageway alongside the building and climbed the back stairs. The remaining three waited outside on the sidewalk.

Sergeant Daniel Groth pounded on the front door. “Who’s there?” came a voice from inside the first-floor apartment. Groth demanded that the occupants open the door, and there were more voices and shuffling inside. Then a pause.

Officer James “Gloves” Davis kicked in the front door commando-style, and he, Groth, and the other three officers in his unit burst into the living room, lighting up the inky darkness with a flash of carbine, pistol and shotgun fire. Simultaneously, the six on the back porch sprang into action. Officer Edward Carmody kicked open the rear door and entered through the kitchen, firing three shots from his revolver. Two of his men followed on his heels, crouching to fire shotgun blasts.

Then the submachine gun rang out; later, the officers would describe what followed as a macabre dance, their fusillade lit up the room like flickering neon, casting the writhing bodies in sharp relief as they fell to the floor, their staccato moans an elegy of grief and unimaginable suffering. Finally, after a few minutes, a pause, followed by two more shots in quick succession from a bedroom, and it was over.

The toll

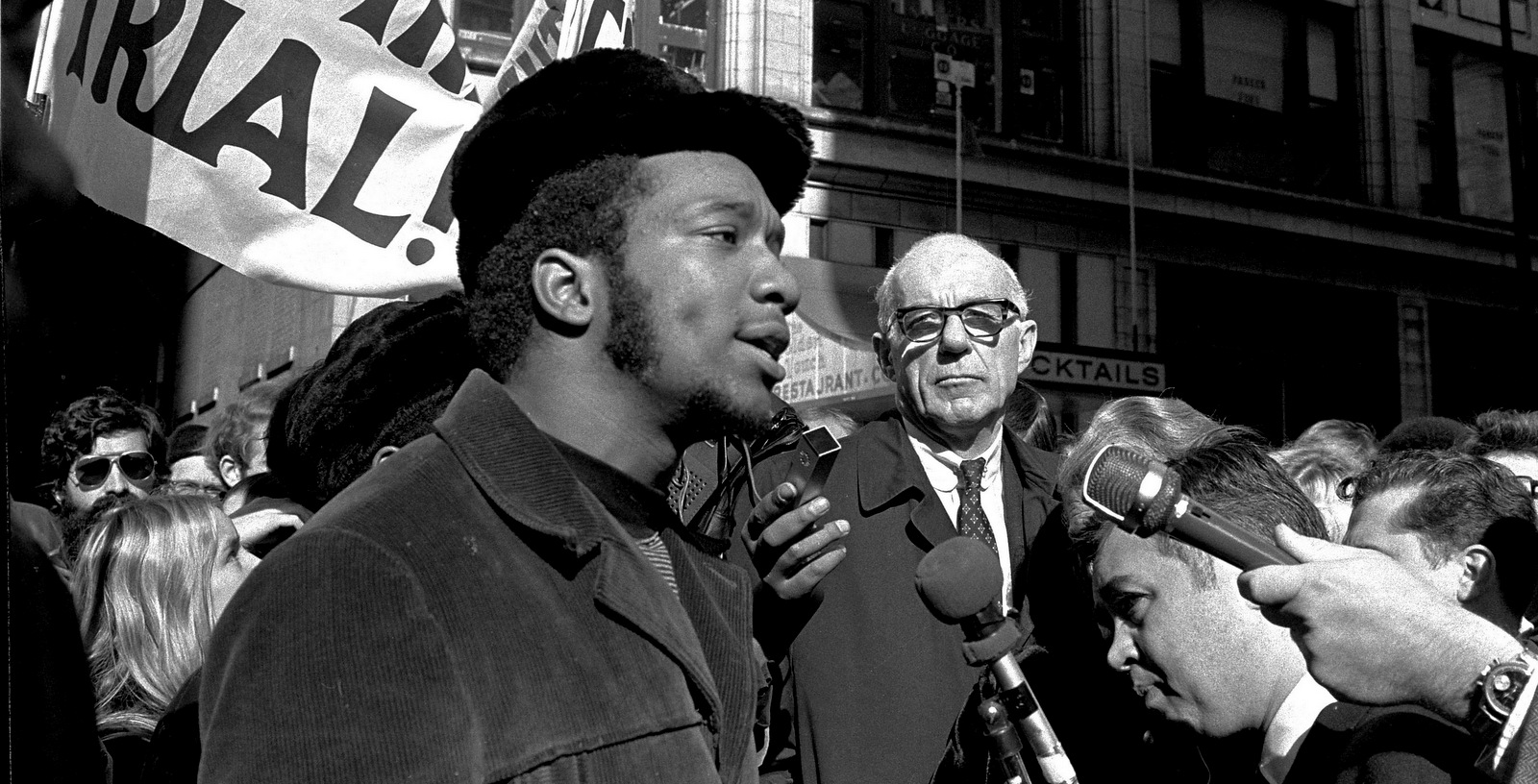

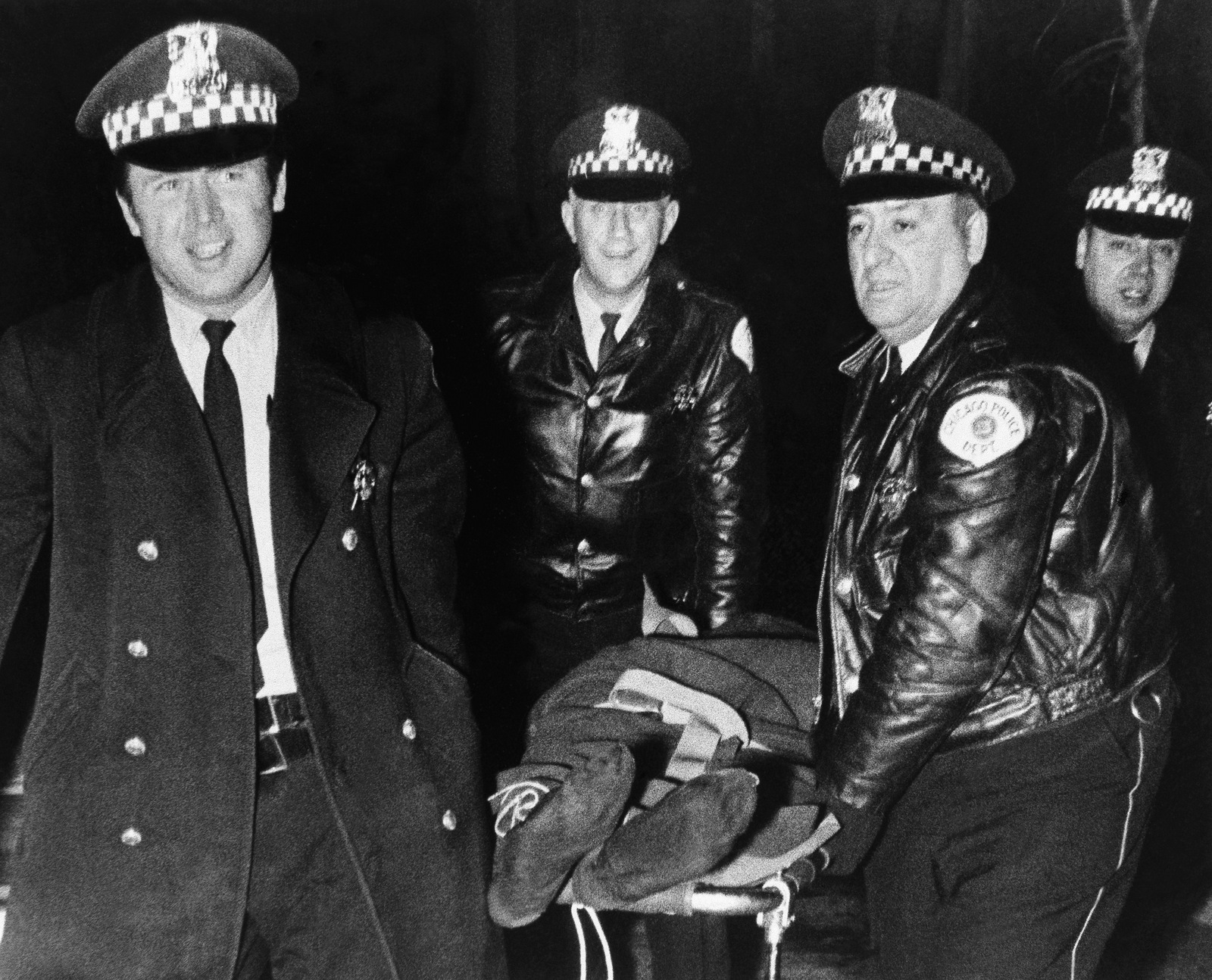

“The premises are under control,” a patrolman who had just arrived on the scene reported over his squad-car radio. Within minutes ambulances and more police cars arrived, hustling two men and a pregnant woman out of the building in handcuffs. Four others were carted out on stretchers, wounded but alive, followed by two corpses: 22-year-old Mark Clark, shot once in the heart, and 21-year-old Fred Hampton, the chairman of the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party, who had been struck once in the chest, once in the shoulder, and twice in the forehead.

As their bodies were loaded into ambulances to be transported to the Cook County morgue, the news of their passing was relayed over the police two-way radio, and later, the downtown dispatcher reported hearing cheers from police cars scattered over the city. Said one officer: “That’s when to get them; when they’re in their beds!”

The turn

The political assassinations at 2337 West Monroe 48 years ago today set in motion a counter-revolution that is the predicate of Americans’ political and material discontent to this day. The grassroots alliance of organized labor, African Americans, and white Leftists – many of them Jewish – that coalesced at the height of the Great Depression was becoming increasingly assertive, demanding everything from higher wages to free college tuition to a welfare state that met everyone’s basic needs.

What had once been an annoyance, when American investors were making money hand over fist, had now become simply intolerable to the super-rich, as European and Japanese manufacturers recovered from the war and began to nibble at U.S. corporate profits.

“It is clear to me, “ David Rockefeller wrote in 1971 to his fellow Chase Manhattan board members, “that the entire structure of our society is being challenged.”

The memo

The Nixon Administration was already on the case. In August of that year, prior to his nomination to the Supreme Court, a courtly, Virginia lawyer named Lewis Powell had submitted a “Confidential Memorandum” to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that articulated a plan for marginalizing liberals on college campuses and in the media. And Nixon’s polarizing Southern Strategy blended seamlessly with COINTELPRO — FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s infamous counterintelligence program designed to criminalize and kill charismatic black radicals — which very much resembled the assassination scheme known as the “surge” that the U.S. military would deploy against Iraqi insurgents nearly 40 years later.

By the time Nixon was sworn in for his first term, Hampton and his comrades in the Party were stitching together an unlikely amalgam of black, Puerto Rican, and white street gangs, white blue-collar workers and college students, and black professionals. So profound was Hampton’s influence that Jesse Jackson would trademark the term “Rainbow Coalition” during his two presidential campaigns, and former Weather Underground activists Bernardine Dohrn and Bill Ayers told me two years ago that they keep in touch with Hampton’s mother and regularly visit his Louisiana gravesite.

“Chairman Fred called us to a lifetime of service to humanity,” said Bruce Dixon, the managing editor of Black Agenda Report, who was an 18-year-old Panther recruit in 1969 . “If we weren’t doing something revolutionary, Fred told us many times, we shouldn’t even bother to remember him.”

In a clear admission of guilt, the Chicago Police department would pay out $1.85 million dollars to settle a civil suit filed by Hampton’s family in 1983 — but for evidence of his martyrdom you need only understand that law-enforcement personnel never sealed off the apartment, as is customary in crime scene investigations, leaving hundreds of Chicagoans to tour the ransacked, pockmarked, blood-stained abattoir, including a state lawmaker named Harold Washington.

The inspired

The scene moved Washington, who was beginning to grow weary of the heavy-handed control exercised by Chicago Mayor Richard J. “Boss” Daley’s political machine. Only three years earlier, Daley had ordered the machine’s black politicians to ignore, if not berate, Martin Luther King Jr. on his visit to the Chicago area to highlight issues of racial discrimination in housing.

After Daley’s death in 1976, a group of black Chicago activists, animated by Hampton’s murder and the Daley machine’s indifference to black and brown neighborhoods, approached Washington about running for mayor in 1982 and, after a bit of a dance, he agreed. Backed by his own rainbow coalition in a city that was roughly divided between Blacks, Whites and Latinos, Washington won.

Despite stiff opposition from white aldermen and state lawmakers, Washington’s administration worked assiduously to cut everyone in on a sweet deal that had previously been reserved for a privileged few. He rescinded a municipal ordinance prohibiting street musicians from panhandling, issued an executive order forbidding municipal employees from enforcing immigration laws, computerized city departments, and extended collective bargaining rights for public trade unions whose rank-and-file members were often kept in the dark about the labor contracts struck between their corrupt leadership and the Daley machine.

Washington also opened up the city’s budget process by holding public hearings around the city, increased the number of women and Blacks at City Hall, capped campaign contributions for contractors doing business with the city at $1,500, and professionalized the city’s workforce by banning patronage hiring and firing — all of which would’ve been unimaginable under the old machine. He even mothballed the city’s limousine, for an Oldsmobile 98.

In winning reelection in 1987, Washington increased his share of the city’s white vote from 8 to 20 percent, with the help of a white political strategist named David Axelrod, who would go on to manage Barack Obama’s 2008 election, and his 2012 reelection, campaigns. “Indeed,” writes the political scientist Jakobi Williams, in his 2013 book From the Bullet to the Ballot:

“Obama’s election as a the forty-fourth U.S. president is a direct result of David Axelrod’s campaign skills which he honed as a member of Harold Washington’s team and which others have also documented was no doubt ‘a defining moment in the formation of his political consciousness.”

The words

Yet while America’s first black president, who arrived in Chicago during Washington’s first term in office, spoke freely of his admiration of the city’s first black mayor, Obama’s Rainbow Coalition was a campaign strategy not a governing one. With his corporatism, hawkish foreign policy, and crackdown on dissenters such as Occupy, Obama’s two-terms in office were far more reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s White House, than of Washington’s city administration, which was informed by Hampton’s socialist views.

The deeds

While Washington reversed public policies steeped in white supremacy, Obama deepened them.

Washington weakened the influence of money in politics; Obama strengthened it.

Washington accommodated immigrants and helped transform Chicago into a sanctuary, while Obama deported more than any president in history.

Washington rewarded organized labor for its efforts to elect him; Obama gave labor unions the cold shoulder, when he wasn’t trying to bust them altogether.

Washington opened space for women, people of color, and even workers in the informal sector trying to make a living any way they could in an enervated economy; on Obama’s watch, the nation witnessed an unemployed black man lynched on a Staten Island street corner merely for selling loose cigarettes.

Washington invoked Fanon, and exhorted people of color to never give up the fight against injustice and oppression; Obama invoked Reagan, trafficked in folklore, and scolded black men for feeding their children cold Popeye’s chicken for breakfast.

Washington embodied Bessie Smith’s Blues, Obama the mediocre hip-hop of Drake.

The arc

Yet, unlike under Washington’s unifying governance, Obama’s share of the white vote fell precipitously in his 2012 reelection.

The contradiction owes itself to the reactionary revolution that began in earnest with Hampton’s state-sponsored assassination. By the time Washington dropped dead at his desk in City Hall in 1987, investors were launching the next step of their insurrection to counter grassroots movements led by figures such as Washington and Hampton with neoliberal black candidates propped up by corporate cash, think tanks, and the academy.

In a 2006 Harper’s Magazine article, Ken Silverstein quoted former White House Counsel Greg Craig saying that he “liked the fact that Obama was not a racial polarizer on the model of Jesse Jackson or Al Sharpton,” and a lobbyist Mike Williams saying that he was “soothed by Obama’s reassurances that he was not anti-business.”

Only months before his death, Hampton seemed to predict the rise of Vichy black politicians like Obama, while explaining why education was integral to the struggle:

If the people ain’t educated, one day, we’ll have Negro imperialists.”

Jon Jeter is a published book author and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist with more than 20 years of journalistic experience. He is a former Washington Post bureau chief and award-winning foreign correspondent on two continents, as well as a former radio and television producer for Chicago Public Media’s “THIS AMERICAN LIFE.”