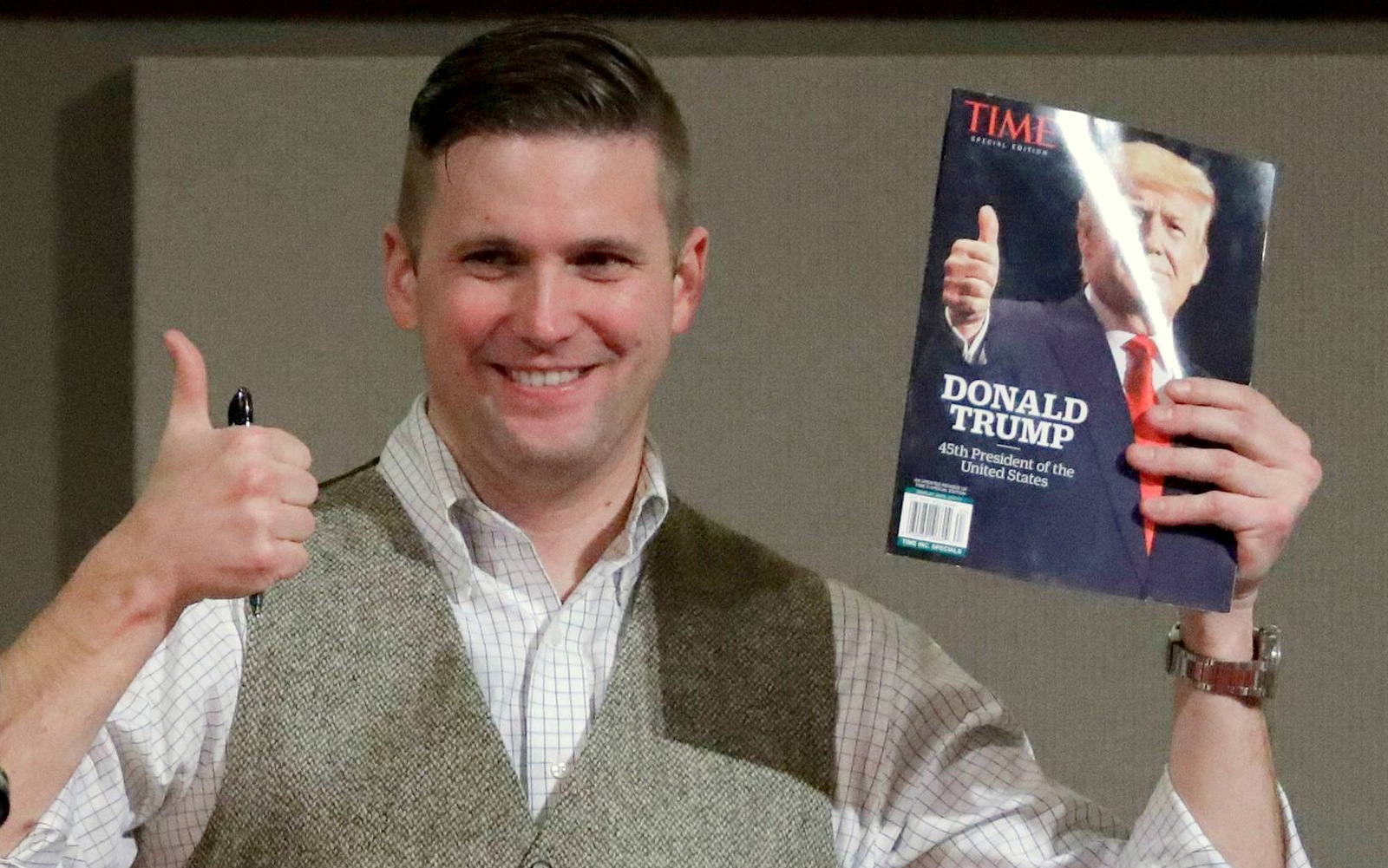

On March 5, the prominent white nationalist Richard Spencer was scheduled to speak at Michigan State University.

The event quickly turned into a bust when only about three dozen people made it inside the building — while hundreds of Spencer supporters and anti-fascist protestors confronted each other outside, throwing rocks and punches. Local police arrested 25 people.

The next day, Spencer’s lawyer Kyle Bristow resigned and quit the white nationalist “alt- right” movement altogether, complaining about the relentless vilification of his work in the media.

The Southern Poverty Law Center previously described Bristow as the “go-to attorney for a growing cast of racists.” He’d set up the Foundation for the Marketplace of Ideas, which he once described as “the sword and shield” of the alt- right. Now the website and Facebook page no longer exist, and there’s been no mention of any new leadership.

Less than a week later, on March 11, Spencer announced in a YouTube video that he was canceling a planned college tour amid increasing violence and low attendance. “Antifa is winning” and rallies “aren’t fun anymore,” Spencer conceded. “We felt that great feeling of winning for a long time. We are now into something that feels more like a hard struggle, and victories are not easy to come by.”

Indeed, as alt-right members seek more of a public profile, coordinated anti-fascist actions and online pushback have intensified, making it harder for them to recruit, host events, and find jobs. They’ve been forced into online echo chambers.

Two days later, the implosion continued. Matthew Heimbach, head of the white supremacist Traditional Worker Party (TWP), was charged with domestic battery for assaulting his stepfather and TWP spokesperson, Matthew Parrott. The two violently confronted each other after Parrott learned of an affair between his wife and Heimbach. Soon after the arrest, Parrot resigned from TWP and took down the website. “I’m done. I’m out,” Parrott told the Southern Poverty Law Center. “SPLC has won. Matt Parrott is out of the game. Y’all have a nice life.”

At one level, the alt-right seems to have succumbed to leadership rivalries and infighting. The Washington Post even reported recently that the movement appeared to be “imploding.”

However, division is not necessarily a sign of collapse. Indeed, such divisions are inevitable in a political movement — and could instead be a sign of intense ideological activity. Even though high-profile leaders like Richard Spencer and Matthew Heimbach have stumbled, white grievance and the far right ideologies that fuel it continue to be nurtured online, and have broken into the political mainstream on both sides of the Atlantic.

European Inspiration

From its inception, the American alt-right has been drawing its ideological, rhetorical, and tactical inspiration from European far-right thought and movements. And there, the trend is toward more tightly controlled, somewhat less explicitly racial branding.

Identity Evropa (IE) is a relatively new, youth-led American white nationalist group that promotes what it calls “ethnopluralism” — that is, ethnic separation — to preserve a mythologized European heritage and white identity from the perceived threat of “Islamicization” and mass migration.

After Charlottesville and under the new leadership of Patrick Casey, IE has been distancing itself from the more extreme elements of the alt-right to control their branding. IE members are now carefully vetted, events are invitation-only, and they use an “identitarian” rhetoric centered on “culture” and “identity” rather than race.

IE’s inspiration comes from the pan-European identitarian organization Generation Identity (GI). Many American far-right activists admire GI for its ability to pull off high profile publicity stunts and bring activists out onto the streets. Discussing North American identitarianism and collective learning between the U.S. and Europe, American far right activist and social media personality Brittany Pettibone told Austrian GI co-leader Martin Sellner (now also her boyfriend) in a video: “We’ve mastered the online activism and you’ve mastered the in-real life activism.”

Last summer, GI activists rented out a ship and sailed out into the Mediterranean to disrupt the work of humanitarian groups saving the lives of migrants. They received financial support and media coverage from a wide range of far-right figures and groups across the world — including former KKK leader David Duke, Canadian “alt-light” vlogger Lauren Southern, Breitbart News, and European Parliament member Nigel Farage.

More recently, GI struck again. In late April, between 80 and 100 activists — including Pettibone, Southern, and Sellner — tried to block a French alpine pass used by migrants. They set up a “border” with plastic wire mesh, rented out two helicopters, and flew drones to surveil the area and rebuked migrants. “The mission was a success,” a GI spokesperson toldthe French newspaper Le Monde. “We successfully brought media and political attention to the pass.” In both actions, stopping migrants was less important than getting international publicity and proving their legitimacy.

Identity Evropa imitates many lower-wattage GI tactics such as banner drops, flash demonstrations, and leafleting campaigns, mostly on college and university campuses. These non-violent actions are then heavily shared online to amplify their impact and visibility. The group also focuses on fostering a sense of community among members through social meetups, hiking trips, fitness clubs, and communal activities.

Organizing Digitally

Although the recent misfortunates have befallen the most extreme and public fringes of the alt-right, the more putatively “moderate” wing continues to propagate and normalize far-right propaganda in the mainstream political discourse with impunity. Right-wing radicals and social media personalities Mike Cernovich and Alex Jones in the U.S., Paul Joseph Watson in the UK, and Lauren Southern in Canada have together over 4 million followers on YouTube alone.

The majority of American extreme right groups are now highly internationalized, and highly active on the Internet. Skillfully using multimedia opportunities and social media, they are able to reach, recruit, and mobilize a wider audience and diffuse far-right propaganda beyond national borders. The internet has given them the opportunity to scale up their activism from the local level to the transnational level, opening up new markets and broadening their audience.

The tech savvy alt-right is not short of options to thwart crackdown efforts led by tech companies and regulators. Extremist groups banned from mainstream crowdfunding platforms like PayPal, for example, have been investing in cryptocurrencies such as bitcoin to collect money and continue their activities free from government control. During his speech at the far-right National Front party convention in France last month, white nationalist Stephen K. Bannon, formerly Donald Trump’s chief strategist, praised cryptocurrency and block-chain technology for their liberating and empowering potential.

Penetrating the Mainstream

Neither the KKK nor white nationalists hold a monopoly on violence, racism, Islamophobia, or nativism. In fact, their bigoted beliefs have long been thriving far beyond the insular world of the far right and are firmly rooted in the broader social and political order.

In her recent book White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide, American writer and academic Carol Anderson traces the legacy of white rage and structural racism in American society. She writes:

White rage is not about visible violence, but rather it works its way through the courts, the legislatures, and a range of government bureaucracies. It wreaks havoc subtly almost imperceptibly. Too imperceptibly, certainly, for a nation consistently drawn to the spectacular — to what it can see. It’s not the Klan. White rage doesn’t have to wear sheets, burn crosses, or take to the streets. Working the halls of power, it can achieve its ends far more effectively, far more destructively.

In this sense, the Republican Party has become a much more powerful instrument of white rage than the alt-right. At the state level, University of Georgia Professor and Far Right in America author Cas Mudde writes, “authoritarianism and nativism run rampant among governors and legislators alike. It is almost exclusively among GOP-controlled states that strict anti-immigration and ‘anti-Sharia’ legislation was introduced. And the vast majority of Republican governors refused to accept Syrian refugees to their state, on the unfounded allegation that they would include terrorists.”

At the federal level, far-right-leaning elected officials in the House and Congress are a minority, albeit a vocal one. In the White House, however, ultra-conservatives are gaining power since problematic far rightists (like Stephen Bannon and Sebastian Gorka) and more establishment-minded “globalists” (like Rex Tillerson, Gary Cohn, and H.R. McMaster) have been purged. Trump’s nomination of John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, well known war hawks and Islamophobes, to key foreign policy posts suggests that this element of the Republican Party is ascendant, at least within the executive branch.

With the nomination of CIA director Pompeo as new secretary of state, “President Trump is playing right into the hands of the radical anti-Muslim movement in the U.S. and abroad,” warns the SPLC. Indeed, Pompeo has close ties with major anti-Islamic groups, such as Act For America, which has lobbied to restrict refugees settlements into the United States. Act for America awarded Pompeo its highest honor, the National Security Eagle award, in 2016.

Bolton’s background is even more problematic. He’s deeply connected with high-profile members of the so-called counter-jihadist movement, such as the president of the right-wing Center for Security Policy, Frank Gaffney. Bolton was also chairman of the anti-Muslim Gatestone Institute, a think tank known for publishing fearmongering articles and fake news about refugees and Islam, right up through March 2018.

Facing external resistance and internal disagreements, the alt-right is having trouble unifying and mobilizing in the streets. However, it continues to be a threat online by skillfully using the Internet to spread far-right propaganda, recruit, raise money, and build transnational solidarity networks.

Carol Anderson advises her readers to pay attention to the logs and kindling, and not get blindsided by the flames. The president’s inflammatory tweets, white nationalists gathering in the streets, and the surge in hate crimes are the visible flames of a rampaging wildfire.

Sometimes, as with Richard Spencer and Matthew Heimbach, the flames threaten to burn themselves out. But the digital campaigns on the Internet and the mainstreaming of identitarian rhetoric are the kindling that bears closer attention.

Top Photo | This Aug. 17, 2017 image from video shows a Confederate flag, right, displayed alongside an Israeli flag and a colonial-era American one in the seventh-floor windows of an apartment in the East Village neighborhood of New York. The flags had been there for over a year, and illuminated at night, but after an Aug. 12 white nationalist rally to preserve a Confederate statue in Charlottesville, Va., spiraled into violence the flags were met with hurled rocks, a punched-out window, a tarp hung over them and legal action before being removed. (PIX11 News via AP)

![]() FPIF is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.

FPIF is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License.