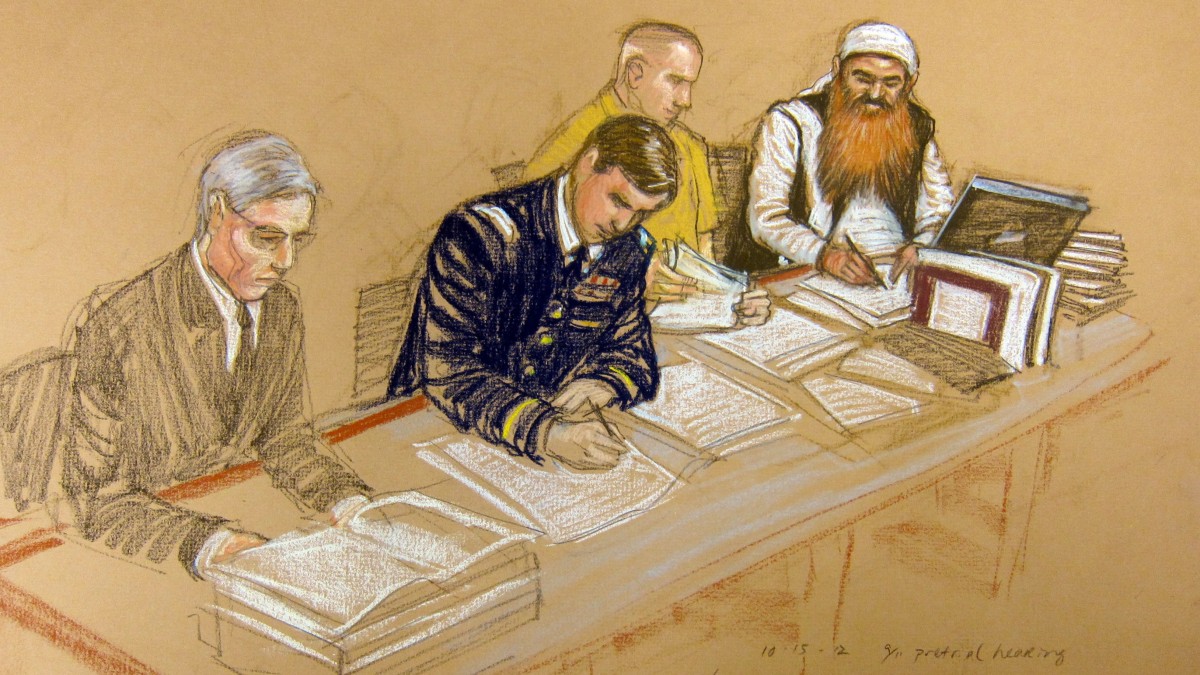

(NEW YORK) MintPress – Last week’s appearance in U.S. military court by the self-proclaimed mastermind of the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, and his four alleged accomplices — his nephew, Ali Abdulaziz Ali; Walid Muhammad Salih Mubarak Bin ‘Attash; Ramzi bin al-Shibh; and Mustafa Ahmed Adam al-Hawsawi — was their first since May.

It was part of an often delayed pre-trial hearing that will help determine how their eventual trial by the Guantanamo military commission will be conducted. One of the key issues: transparency.

In April, the government asked the military judge to enter a “protective order” contending, among other things, that because the defendants were “exposed” to the CIA’s classified rendition, detention and interrogation program, anything they said about it in court could be kept from the public.

The government wants to implement a 40-second delay of the audio feed from the soundproof courtroom, during which a censor can use “white noise” to block the public from hearing defendants’ testimony about the CIA’s torture program.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has fought against the plan, citing the public’s constitutional right to know what takes place during the trial.

In a May filing, it wrote, “The public’s right of access to these military commission proceedings is mandated by the First Amendment, and may only be overcome if the government presents evidence of a substantial likelihood of harm to an overriding government interest.”

During the latest hearing, Hina Shamsi, head of the ACLU’s National Security Program, argued its case: “Every day courts around our country deal with classified information without the need to build a censorship chamber. Courts deal with hundreds of sensitive national security and terrorism cases without the need to build a soundproof wall between the courtroom and the American public.”

Now back in New York, Shamsi spoke with MintPress, saying, “There is an ongoing debate at home and abroad about how fair and transparent the conditions at Gitmo are. A decision on censorship won’t resolve that, but if the commissions are organized around censorship, they will not be seen as legitimate.”

Controversy over commissions

Human rights advocates have long contested the establishment of military tribunals for prosecuting detainees held in the Guantanamo Bay detention camp.

On Nov. 13, 2001, President George W. Bush announced that certain non-citizens — those whom the president deems to be or to have been members of the al-Qaida organization or to have engaged in, aided or abetted, or conspired to commit acts of international terrorism that have caused, threaten to cause or have as their aim to cause, injury to or adverse effects on the U.S. or its citizens — would be subject to detention and trial by military authorities.

Five years later, on Sept. 28 and Sept. 29, 2006, the Senate and the House of Representatives, respectively, passed the Military Commissions Act of 2006, allowing the commander in chief to designate certain people “unlawful enemy combatants,” thus making them subject to military commissions, where they have fewer civil rights than in regular trials.

“Military commissions were set up to provide a second tier for justice,” asserts the ACLU’s Shamsi. “As long as we continue to use them, the rules are less fair than those in our central courts. Given the flaws they contain, they will serve neither justice nor our national security.”

While still a member of the Senate, Obama agreed. During the 2008 presidential campaigns, then-candidate Obama told a crowd of supporters at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C., “As president, I will close Guantanamo, reject the Military Commissions Act and adhere to the Geneva Conventions.

“Our Constitution and our Uniform Code of Military Justice provide a framework for dealing with the terrorists. … Our Constitution works. We will again set an example for the world that the law is not subject to the whims of stubborn rulers, and that justice is not arbitrary,” he continued.

“I will reject a legal framework that does not work.There has been only one conviction at Guantanamo. It was for a guilty plea on material support for terrorism. The sentence was nine months. There has not been one conviction of a terrorist act. I have faith in America’s courts, and I have faith in our (Judge Advocates Generals).”

Indeed, just days after being sworn into office, Obama issued an executive order halting the military commissions at Guantanamo while he set up a task force and ordered a review of the more than 200 cases there to determine who should face criminal prosecution as part of a larger effort to permanently close the facility by January 2010.

But on May 15, 2009, Obama changed course and announced that his administration would resurrect the military commissions. In a three-paragraph statement released after the announcement was made, he said, ”Military commissions have a long tradition in the United States. They are appropriate for trying enemies who violate the laws of war, provided that they are properly structured and administered.”

“Congress is at fault,” claims Shamsi, “Obama wanted to do the right thing by having the cases heard in federal courts, where they belong, but Congress sought to tie the administration’s hands and the administration went along with the restrictions.”

According to an investigation by Truthout.org, his about face also followed months of pressure from the Defense Department and National Security officials.

Enhanced interrogations

Republicans had also levied scathing attacks on the president and the Justice Department for their decision to release the Torture Memos drafted by Bush.

The memos related to the Bush administration’s authorization and use of certain severe interrogation methods such as hypothermia, stress positions and waterboarding after 9/11.

The techniques were used by the CIA and the Department of Defense in Guantanamo as well as secret prisons and Abu Ghraib in Iraq on thousands of prisoners, including Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, Abu Zubaydah and Mohammed al-Qahtani.

There was intense public debate over the legality of the methods and whether or not they had violated U.S. or international law.

The United Nations special rapporteur on torture, Juan Mendez, stated that waterboarding is “immoral and illegal” and constitutes torture. In 2008, 56 House Democrats asked for an independent investigation.

Meanwhile, the CIA destroyed many videotapes depicting prisoners being interrogated, saying that what they showed was so horrific they would be “devastating to the CIA” and that “the heat from destroying is nothing compared to what it would be if the tapes ever got into public domain.”

In 2009 both Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder stated some of the techniques are torture and repudiated their use. Yet they declined to prosecute CIA, DoD or Bush administration officials who authorized the program.

Too much information?

Although the government did not contest the ACLU’s position that the public has a First Amendment right to access the military commission proceedings, it asserted that its proposed restrictions on what it can hear are necessary to protect national security.

Nonsense, maintained the ACLU’s Shamsi. “We know such controversial information as the fact that the CIA waterboarded (defendant Khalid Sheikh) Mohammed 183 times. We know that the CIA used beatings, forced nudity, threats against family members, including children, stress positions, deprivation of food,” she argued at the hearing.

Speaking to MintPress, Shamsi maintains, “There can be no compelling interest in hiding from the public information from the defendants’ mouths that’s already been widely disseminated.”

In September, the government modified its initial proposal to include a provision defining as “classified” the defendants’ own “observations and experiences” of their illegal treatment and CIA black site detention.

Says Shamsi, “The government has no legitimate interest in censoring the defendants’ own thoughts and memories. It has no legal authority to classify the defendants’ own accounts of government misconduct.”

She tells MintPress that the judge has not yet ruled on the government’s proposed order and the ACLU’s objections to it, but is expected to do so within a matter of days.