Fifty years ago, a remarkable campaign took place to challenge the notion of white supremacy in one of the nation’s most overtly racist states. Over a 10-week period, more than 1,000 out-of-state volunteers — mostly white college students from the North — joined thousands of black Mississippians in one of the largest voting registration drives in American history.

The campaign was officially known as the Mississippi Summer Project, but it is remembered by history as Freedom Summer.

With only 6.2 percent of the state’s black population registered to vote as of 1962, Mississippi stood as the most vote-disenfranchised state in the country, prompting the campaign’s organizers to use the state as a test model for future registration drives in other states.

Prior to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many Southern states engaged in active disenfranchisement against blacks through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests, stringent residency requirements, and physical and economic harassment — including lynchings. To register to vote in Mississippi, for example, one had to pass a 21-question test based on the interpretation of the state constitution. This was a two-fold attack: voting access depended on education, and education was actively and consciously denied to the Mississippi black community.

The effort to change the status quo in Mississippi was met with extreme and violent resistance from state and local governments, the police, the White Citizens’ Council, the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, the Ku Klux Klan and a number of ad hoc associations. During the 10-week campaign, 80 Freedom Summer workers were beaten, 1,062 individuals were arrested, 37 churches and 30 black homes and businesses were bombed or burned, and four people suffered critical wounds.

Martyrs

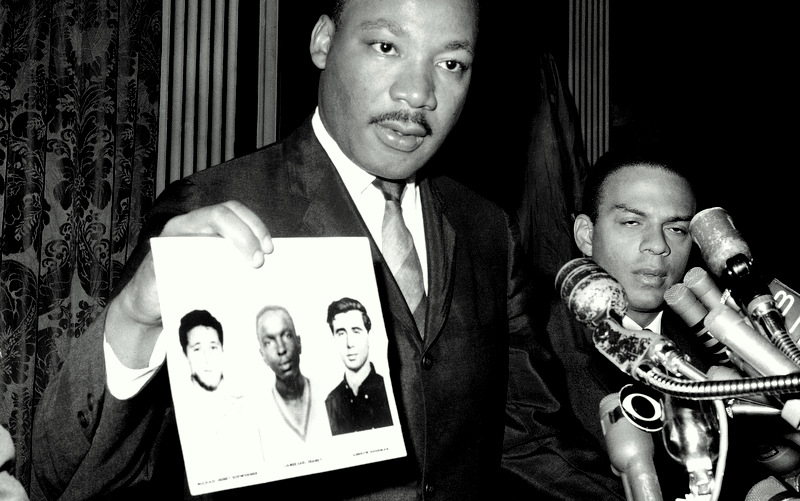

Freedom Summer was remembered most for the events of June 21, 1964, when three Congress of Racial Equality members were arrested by Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, a member of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, for allegedly speeding and participating in the burning of a church.

Upon denying a phone call to CORE activist James Chaney, organizer Michael Schwerner and volunteer Andrew Goodman, and saying he would lie about the three being held in jail, Price released the men that evening after they paid the speeding fine.

Then Price followed them to just before the Lauderdale County border, where he ordered the three into his squad car. Followed by two cars of Klansmen, the deputy sheriff drove to a deserted area on Rock Cut Road. The Klansmen chased and beat Chaney, who was black, before shooting all three — Schwerner and Goodman at point-blank range, and Chaney three times from various angles.

Price returned to the police station and the Klansmen buried the three bodies under an earthen dam under construction.

The resulting media coverage of the disappearance of the three men brought attention not only to the Freedom Summer campaign, but to the “closed society” of Mississippi. The state tried to stall the search for the men, it de-emphasized the search’s importance — calling the men’s disappearance a hoax — and later refused to prosecute the murders.

The search for the Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman turned up the bodies of eight other murdered black men — one of whom was found wearing a CORE T-shirt and two who were identified as Alcorn A&M students who had been expelled for participating in civil rights protests.

The fate of the black community, 50 years later

Freedom Summer’s success in terms of increasing the number of black registered voters in Mississippi was modest, at best, but it did make national news and forced race into the national conversation.

Even 50 years later, it’s difficult to say with certainty whether the fate of black Americans has improved since the campaign.

“Freedom Summer and the civil rights movement catapulted black folks and poor whites just with the major legislation that came out of the movement, particularly the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1965 Voting Rights Act,” Lecia Brooks, outreach director for the Southern Poverty Law Center, told MintPress News.

“These pieces of legislation enfranchised thousands to the right to vote. But, if we were to look at the state of the African-American through the lens of today, that right is being infringed upon again, but we are still not where we were before the 1965 Voting Rights Act.”

Recent issues have raised suspicions that the minority vote is coming under attack again. For example, a rash of Southern states have passed voter disenfranchisement laws since the Supreme Court overturned the existing preclearance coverage formula of Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act last year. This section — which required states and communities with historical records of disenfranchising the vote against minorities to preclear any changes to their voting laws or procedures with the Justice Department — served as a primary hedge against potential disenfranchisement of the minority vote.Such disenfranchisement has been reflected in the rise of the use of voter monitors to discourage the black vote, as in the recent Mississippi Republican Senate primary run-off.

This suspicion is heightened by recent analyses suggesting that the Republican Party can no longer win the presidency without significant support from minority communities. With the minority-majority crossover to happen “within the next couple of years” and with the U.S. expected to have a Latino majority by 2043, many suspect voter disenfranchisement efforts to become more pronounced as the GOP grows more desperate.

However, the larger and more immediate indicators of black American progress lie in the attainment and wealth disparities between blacks and non-blacks. The unemployment rate for blacks and the differences in the marriage rates among the races are at pre-1963 levels, while the wealth disparity between whites and blacks — in dollar terms — are at pre-Great Depression levels. According to Pew Research, as of 2010, the average white American household held $783,224 in assets, compared to just $154,285 held by black households.

While black Americans are making more than they did in 1963, they are also receiving a smaller portion of the national collective wealth. According to a 2013 Brandeis University report, for example, not only is home ownership lower among blacks than whites, but the homes owned by blacks appreciated less over a 25-year period than white-owned homes, carried greater mortgage debt and were subject to a higher foreclosure rate.

“Extreme wealth inequality not only hurts family well-being, it hampers economic growth in our communities and in the nation as a whole,” read the Brandeis report. “In the U.S. today, the richest 1 percent of households owns 37 percent of all wealth. This toxic inequality has historical underpinnings but is perpetuated by policies and tax preferences that continue to favor the affluent. Most strikingly, it has resulted in an enormous wealth gap between white households and households of color.”

A national blindness

Meanwhile, as Neal A. Lester, Foundation Professor of English in African-American Literature at Arizona State University and director of Project Humanities, points out, there is a growing cultural blindness to the issues surrounding race in this country.

“What alarms me, as I look at the next generation, is that they are not looking at nuance, they are not looking at the ways in which people are making decisions and using social media to attack others — such as Joel Ward, who after making the winning goal in the play-off, was immediately attacked on social media, calling him that ‘n-word’ and suggesting that they need to bring lynching back,” Lester told MintPress. “Or, you see people that disagree with President Obama’s policies attack him and the First Family personally.

“This is not coming from people in their sixties; it is coming from teenagers. All of this and this use of the ‘n-word’ without consequence suggest to me that this younger generation believes that this world is only about now and their lives, and that this generation has become way more apathetic and way more narcissistic. That leads to this danger of thinking that racism and classism and homophobia and agism — all of these elements that exist under the umbrella of privilege — don’t exist, when, in fact, they do.”

Among those who study race relations, there is a common argument that the process of creating a “color-blind” society actually led to the situation the nation is dealing with today. Many of those who grew up during the civil rights movement taught their children that “everyone is equal and everyone is the same.” This moral, however, directly undercuts the truth: everyone is equal, but everyone is not treated equally. Well-meaning parents, in effect, stripped the language of the crisis from the vocabulary of the next generation, leaving this new generation unprepared to deal with the issues of inequality in any other way but as a foreign notion that bears no relevance to their worldview.

Freedom Summer today

It can be argued that the lack of visual, centralized leadership may be to blame for the state of things today. Following the end of Freedom Summer, permanent, local-based and -centered groups took over to encourage community-based political growth. An example of this was the development of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which sought to replace the Mississippi Democratic Party as the state’s official Democratic association.

Today, despite the fact that most of the Freedom Summer organizations have long since collapsed, Mississippi — like many Southern states — has one of the highest concentrations of elected black local and county officials in the nation. However, due to redistricting and other efforts, Mississippi — and the South as a whole — ranks among the lowest concentrations of national and statewide elected office-holders of color.

This inability to translate local political gains to the state and national platforms begs questions on whether the lack of a national leadership figurehead in the black community has interfered with the community’s ability to consolidate its political will.

“Movements of communities and people should always be based on the needs of the individuals most affected,” Derrick Johnson, state president of the Mississippi branch of the NAACP, told MintPress. “They should not be driven by national interests that may not — over time — align with the needs and interests of the communities that they purport to represent.

“In the ebb and flow of organizations, there will be many to come and many to go. The real question for a state like Mississippi, as well as other communities across the country, is if they are strategically focusing on how to expand democracy and how best to create participation in a democratic society free of barriers of race.”

Ultimately, it may be that Freedom Summer never ended. While the issues facing the America’s black community have never been so poignantly stacked against the individual or so intimidating, efforts to raise awareness and to move forward have never been so fervent. The movement has since moved away from being based on personalities or national organizations, and instead moved toward the communities in which the change would have the greatest effect.

With communities working on the local level to protect previously won gains, while also fighting for improved access to and participation in the political sphere and economic achievement for the future, the people themselves are responsible for their empowerment — and this may have been the true goal of Freedom Summer.

As the number of victories along the path of full political and economic enfranchisement expands and the obstacles ahead become more pronounced, it is increasingly clear that Freedom Summer wasn’t so much a 10-week experiment, as the beginning of a 50-years-and-counting campaign. Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman were not so much victims of an isolated moment in time, but martyrs for a crusade that continues, even now, to define the “American Experience” and the black person’s place in it.

“Freedom Summer is an example of how when local people strategize to impact local policies in ways that it can have a national impact,” said Johnson.