On July 24, it was revealed that Transparency International’s New Zealand wing had enlisted the specialist advice of some of the country’s biggest, most notorious lobbying firms on improving ethical standards in the political and corporate lobbying industry. A local businessman, who’d independently offered to assist TINZ in cleaning up the sector, blew the whistle.

Expressing “astonishment,” they compared TINZ’s consultation of high-ranking lobbyists on how to clean up their own industry as akin to “police recruiting gang members to determine new rules on pursuit of fleeing drivers.” Yet, anyone familiar with Transparency International’s history would hardly be surprised.

Founded by World Bank apparatchiks in 1993, Transparency International (TI) has relentlessly exposed public sector corruption in the Global South while leaving government-enabled criminality in rich nations unexamined. In other words, it is a means of perpetuating privatization overseas for the benefit of Western investors. Accordingly, the organization is financed by a welter of major corporations, including firms implicated in industrial-scale corruption and tax evasion, such as Google, Microsoft, and Siemens.

The mainstream media never subject Transparency International or its dubious annual Global Corruption Barometer and Corruption Perceptions Index to critical scrutiny, invariably giving prominent billing to the organization’s regular publications and pronouncements. Nonetheless, a report on the TINZ controversy by New Zealand public radio contained a remarkable disclosure. The division was noted to receive sizable funding from several local government sources, including Canberra’s equivalents of the CIA and NSA, the Security Intelligence Service and the Government Communications Security Bureau.

TINZ’s CEO defended this sponsorship, arguing spying agencies “have a strong interest in fighting corruption – that is one of their primary issues, the things that they do.” Western intelligence services have indeed been heavily focused on “fighting corruption” in recent years. As we shall see, though, the objective is to weaponize the issue in order to demonize and destabilize “enemy” governments and perhaps even foment regime change. Frequently too, Transparency International has played a starring role in these efforts.

‘Complex and Controversial’

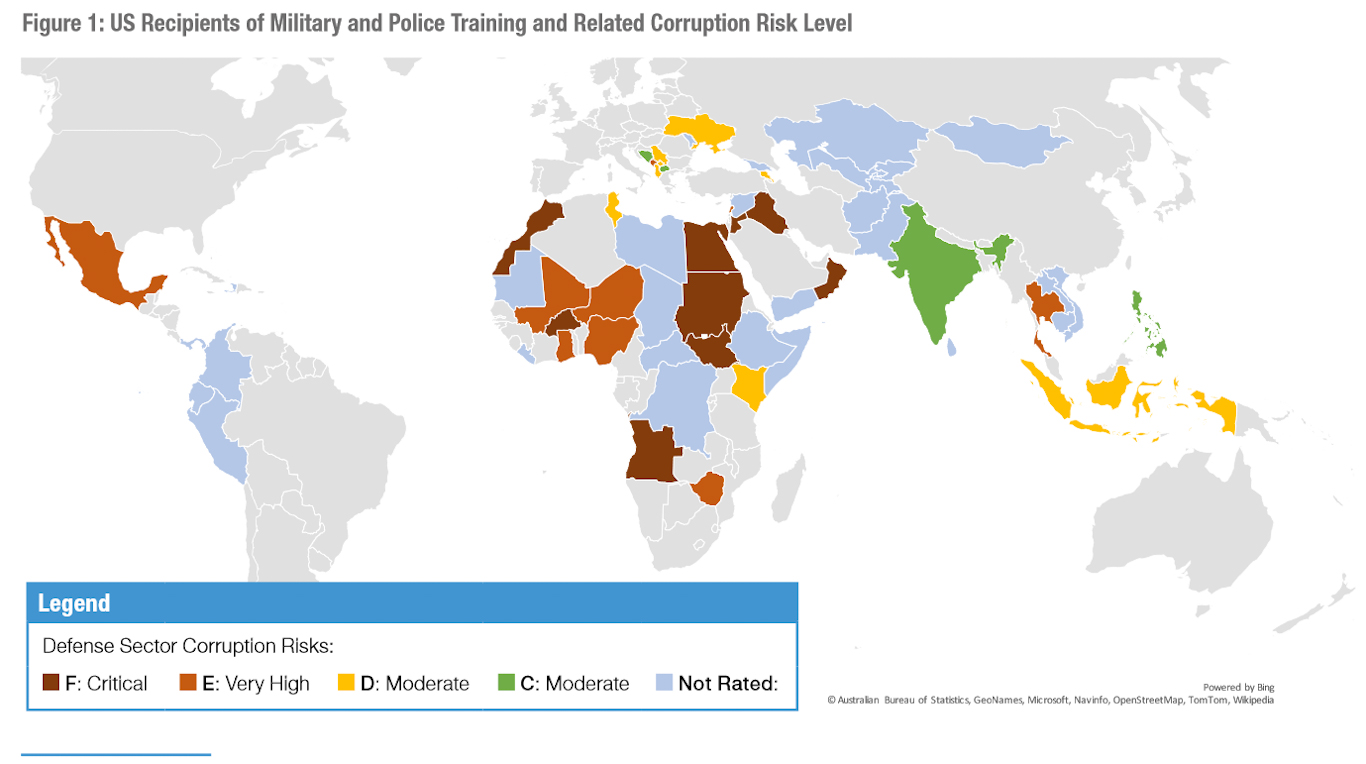

In 2013, TI published its first Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index, measuring levels of alleged corruption in the defense sectors and militaries of 82 countries. Many of the governments that ranked poorly criticized the findings, and report methodology, under which 77 “technical questions” were posed to local state officials and representatives of think tanks and universities.

As Mark Pyman, then-head of TI UK’s Defence and Security Programme, explained in response, simply not answering these questions was sufficient to bag a country a negative rating. These queries ranged from frivolous – such as whether a country’s defense chiefs “publicly commit” to fighting corruption – to intensive interrogation of military operations and procurement. It’s quite understandable government officials in, for example, Venezuela – among the Index’s worst performers that year – would be very wary of such approaches.

Those anxieties would no doubt be maximized by TI’s Defence and Security program being at that time funded by NATO and a number of Western governments. Since then, despite not generating much in the way of press coverage, it has become a standalone division of TI, with its own website, issuing a steady stream of reports on corruption issues in the international defense sector.

These publications deploy lofty rhetoric and frequently identify very serious issues and problems. But their recommendations are typically concerned with making the art of invasion and killing more efficient, ensuring that NATO state weaponry, technology and skills can’t be accessed by the “wrong” governments, and encouraging slightly enhanced state oversight of certain areas, such as private military companies. And only then because Western governments might lose money, and risks could be posed to their “foreign policy interests.”

Measures to seriously curtail the most dangerous, innate excesses of the international arms industry, let alone prevent conflict in the first place, are never on the agenda. Moreover, just as TI has a blindspot to Western private sector corruption, so too does TI Defence and Security incongruously overlook the utterly routine graft and villainy engaged in by U.S. and European governments and defense contractors to market and sell lethal wares overseas.

Mark Pyman himself made this agenda very clear in 2007 when the furor over the Al-Yammah arms deal was reaching a fever pitch. Signed in the mid-1980s between Britain and Saudi Arabia, it remains the former’s largest-ever weapons export agreement, netting London 600,000 barrels of crude oil per day and BAE Systems many billions of pounds ever since. Government officials on both sides – and their relatives – improperly profited from the deal, but multiple criminal investigations were scuttled.

Pyman wrote to “The Guardian” that year arguing a “joint Saudi-British committee” to examine the two countries’ defense relationship should be founded. Albeit, “one that is focused forward” and only concerned with “ensuring the probity” of future arms deals. He actively warned against “trawling through the history” of Al-Yammah’s “complex and controversial” as it “may well have an insubstantial outcome.”

Meanwhile, to this day, the official websites of numerous British embassies abroad openly encourage homegrown arms dealers to trade with local markets and offer guidance on “how to do business” there. This extends to providing contact introductions, privileged market information, and even the British Ambassador’s private residence for business lunches and receptions “with targeted top management from government and/or private entities” in the defense sector. All for an appropriate fee, of course.

‘Non-Lethal Engagement’

This background is vital to consider, as TI UK’s Defence and Security Programme has a formal, albeit largely concealed, relationship with 77th Brigade, the British Army’s psychological warfare division. The Winter 2017 edition of Corruption Cable, TI UK’s quarterly newsletter, has a dedicated section on this suspect bond, through which members of the shadowy and highly controversial military unit are regularly seconded to the Programme for a year.

A 77th Brigade secondee was quoted at length praising the Programme, which provides “opportunities [that] extend beyond relating to the Army-related work.” This included producing material for “case studies, reports and teaching packages”:

All of this will eventually benefit the Army, as I take the knowledge I have gained back with me and the value of being surrounded by knowledgeable and passionate people cannot be underestimated!”

This sounds wholesome enough, although as the secondee openly stated, the 77th Brigade’s core components include the foremost media and psychological operations divisions of British military intelligence. As such, they added, the unit is concerned “with using non-lethal engagement and non-military levers to adapt behaviours of opposing forces and adversaries.”

As was revealed during the COVID-19 pandemic, these “forces and adversaries” include average social media the world over, whose perceptions and behavior the unit seeks to “adapt” through propaganda, manipulation and informational subterfuge. It seems all but inevitable that knowledge 77th Brigade operatives gain while seconded to TI – which may include the answers to Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index questions provided by foreign defense officials – is exploited for psychological warfare purposes.

This analysis is reinforced by a series of leaked documents related to the internal workings of Integrity Initiative, a British intelligence black propaganda unit. Among the papers is a proposal for a government-funded program exposing state corruption in the West Balkans, which names none other than Mark Pyman alongside a British Army Brigadier who founded TI’s Defence and Security division, and two 77th Brigade veterans, including its founder-and-chief Alex Aiken, as potential project staff.

Aiken’s accompanying biography notes that he was personally responsible for “forming the strategic relationship with Transparency International,” a clear indication of how valuable and significant the secondment program was considered at the highest levels of the British Army and 77th Brigade. Integrity Initiative operative Euan Grant was also proposed for the project. Other leaked files indicate he concocted a variety of wide-ranging plans for “information operations,” exposing purported Russian state and corporate corruption.

One scheme entailed sourcing damaging intelligence on Russian organized crime activities from major financial institutions, then publicizing the yield via a number of sources, such as journalists at major publications and the producers of the hit TV show McMafia, but “especially” the 77th Brigade. One of Grant’s proposed information sources was HSBC, a major British bank linked to every form of corruption and malfeasance imaginable globally. Coincidentally, his contacts there included former high-ranking MI5 and MI6 officials.

Boys from Brazil

One might argue that even if corruption by governments, businesses, organizations, and individuals is exposed via intelligence agency “information operations,” the ends justify the means. After all, corruption is a serious crime for which the perpetrators should always be held accountable to the full extent of the law but rarely ever are.

Yet, the public and media appetite for righteous defenestrations of corrupt officials can easily be exploited for malign ends. This is precisely why Western intelligence agencies have so determinedly sought to foment such an appetite over many years.

In November 2009, the Brazilian Federal Police Agents Association’s fourth congress was convened. Among the speakers was Judge Sergio Moro, a minor celebrity for his recent role in busting a major money laundering operation, who led a panel on “Fighting Corruption and Organized Crime” He argued for changes in the law and more judicial autonomy to facilitate the prosecution of white-collar crime in the country.

Also present was American prosecutor Karine Moreno-Taxman, who was then based in the U.S. Embassy in Brazil. She led a panel advocating for Brazilian authorities to maintain an informal system of collaboration with their American counterparts, circumventing formal cooperation structures as set out in international treaties. Along the way, she stressed the need for manipulating public opinion in prosecutions of high-profile figures to engender loathing of those being investigated:

Society needs to feel that that person really abused the job and demand that he be convicted. If you can’t bring this person down, don’t do the investigation.”

Five years later, Moro and Moreno-Taxman were key figures in Operation Lava Jato. Publicly presented as a crusading anti-corruption effort heralding a new dawn in Brazil, in which democracy and the rule of law reigned supreme, in reality, it was a fraud directed by the CIA, FBI, and U.S. Department of Justice (DoJ). The objective was to destroy the country’s most profitable companies and prevent the left from retaking power.

For years, Lava Jato prosecutors – all graduates of FBI and DoJ training programs – along with Moro, who oversaw the effort, were hailed by Western journalists and officials. Moro was even named one of Time Magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” in 2016. In December of that year, TI gifted the Lava Jato team its annual “Anti-Corruption Award,” which “honours remarkable individuals and organisations worldwide…who expose and fight corruption.”

Neither “Time” nor TI acknowledged that months earlier, local media revealed Moro illegally wiretapped former Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s defense team. This was one of many egregious criminal tactics in which the judge, and Lava Jato prosecutors, routinely engaged. In fact, TI Brazil ignored a great many damaging disclosures about investigators, instead giving the Operation blanket, fawning coverage, and documenting and praising their crusading efforts every step of the way.

Following Moreno-Taxman’s prescription that “society needs to feel that that person really abused the job and demand that he be convicted” to the letter, Lava Jato prosecutors went to enormous lengths to demonize Lula. In regular press conferences, prosecutors presented laughable PowerPoints depicting him at the epicenter of a grand, labyrinthine regional and international corruption conspiracy through which the former President was intimately implicated in every serious crime imaginable.

In July 2017, TI welcomed Lula’s conviction on corruption charges as “a significant sign the rule of law is working in Brazil and that there is no impunity, even for the powerful.” It added that prosecutors and judges involved in the probe were “facing attacks from all sides…proof corruption does not distinguish between ideologies or political parties.”

‘Democratic Credentials’

Yet, Lava Jato did have a heavily partisan bias. Investigations by “The Intercept,” based on the hacked communications of investigators, starkly exposed from June 2019 onwards the Operation’s fraudulent nature and intimate ties to U.S. intelligence. One prosecutor dubbed Lula’s incarceration, which disqualified him from the race and laid the foundations for far-right Jair Bolsonaro’s resultant victory, “a gift from the CIA.”

In response to these bombshell revelations, TI quickly issued a statement claiming to be “closely following the reporting.” Strikingly though, rather than condemning how Lava Jato unlawfully weaponized corruption for malign ends, the organization instead primarily praised the Operation. It had claimed TI “revealed criminal schemes” and “challenged powerful politicians and businesspeople” while “bolstering a positive anti-corruption dynamic in Latin America, which has produced significant results in several countries.”

While TI conceded Lava Jato prosecutors needed to explain “alleged irregularities and violations of the principles of equality of arms and impartiality” revealed by “The Intercept,” it considered “rigorous investigation of the violation of private communications” to be “equally crucial.” A cynic might suggest TI was concerned subsequent disclosures would directly implicate the organization in Lava Jato’s malign machinations, which they did.

Hacked communications show TI Brazil director Bruno Brandão enjoyed a very warm relationship with lead Lava Jato prosecutor Delton Dallagnol, and he was a member of several messaging app groups in which various connivances were formulated and discussed. Furthermore, Brandão personally helped produce a TI Brazil-approved list of candidates in the 2018 election who avowedly shared Lava Jato’s ethos, along with a ranking of politicians according to their legal problems and purported commitments to democracy.

Brandão has since attempted to distance himself from Lava Jato, claiming he and TI had simply made a mistake “in believing that the leaders of Lava Jato had democratic credentials.” Yet, in April 2022, Brazil’s Federal Auditing Court and Public Prosecutors Office sought to open an investigation into TI Brazil for having illegally collaborated with prosecutors. There are suggestions the organization may have stood to benefit financially from that relationship.

Questions can only abound as to whether Brandão – and by extension TI Brazil – was in on the con all along. In 2016, he made dozens of appearances in national and international media, denying that a coup was in swing after Dilma Rousseff was improperly deposed due to bogus corruption allegations. Immediately after she left office, Brasilia started auctioning off its offshore oil reserves to foreign buyers. Two of the largest beneficiaries were Shell and ExxonMobil, both donors to Transparency International.

This was just one of many examples of Lava Jato’s economic destruction. The Operation created a climate in which even vague insinuations of impropriety could damage major companies if not entire industries. It paralyzed construction, while millions of jobs and tax revenues were lost, causing the country’s GDP to contract by at least 3.6%. For the CIA, which wanted to reduce Brazil to its impoverished, authoritarian, and easily exploitable Cold War status, this was precisely the point.

Feature photo | Illustration by MintPress News

Kit Klarenberg is an investigative journalist and MintPress News contributor exploring the role of intelligence services in shaping politics and perceptions. His work has previously appeared in The Cradle, Declassified U.K., and Grayzone. Follow him on Twitter @KitKlarenberg.