The Indian-born British novelist Salman Rushdie is back in the news, but this time over the release of his latest book, “Joseph Anton: A Memoir.” In his latest work, Rushdie looks at his life during the years he lived in hiding after Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa that called for his death after he allegedly insulted the prophet Muhammad in his controversial novel, “The Satanic Verses” (a fatwa is a legal opinion or ruling issued by an Islamic scholar). Ironically, Rushdie’s memoir comes out on the heels of the YouTube video clip, “Innocence of Muslims” that has enraged Muslims around the globe for portraying the prophet as a womanizer and pedophile.

When “The Satanic Verses” came out, I was based in Dubai for an international news agency and was in the process of trying to reopen our news bureau in the Iranian capital, Tehran.

After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, many news agencies, including the one I worked for, closed down and foreign staff were told to leave the country. Even though news agencies continued to report through their local staff, the stories and photographs produced were heavily censored.

In the late 1980s the Iranian government began to relax restrictions on the foreign media. My editors asked me to reopen the bureau and carry out all the necessary logistics to make it operational. Over the course of a six-month period I went back and forth to Iran trying to pave the way for either myself or another foreign staffer to be based in Tehran. In the end, all my efforts proved fruitless and it wasn’t until years later that foreign correspondents could report again from inside the country.

In 1989, during one of my trips, I received a call from an Iranian journalist friend who said that he would share a big “scoop” with me if I agreed to a couple of conditions. He wanted me to take his film out of the country once the story was finished and ship it to his agency from Dubai. Then he told me to instruct my news agency not to let either Time magazine or Newsweek publish any of the photos I took of that same event (my friend had an assignment for Newsweek and he wanted to make sure that my images would not compete with his).

After I agreed to his conditions, he said that he would pick me up at my hotel the following morning. That night, I lay in bed staring at the ceiling trying to figure out what could possibly be happening to be considered such a big “scoop.” The war with Iraq had ended six months earlier, the 10-year anniversary of the Islamic revolution had passed and now Tehran seemed so quiet.

Bright and early the following morning my friend picked me up and, as we headed to the center of Tehran, he explained to me what the story was about. He said that Imam Khomeini had just issued a fatwa condemning Salman Rushdie and his editors to death over the publication of a book that insulted the prophet Muhammad and that there was going to be a huge rally in the center of the city calling for Rushdie’s death.

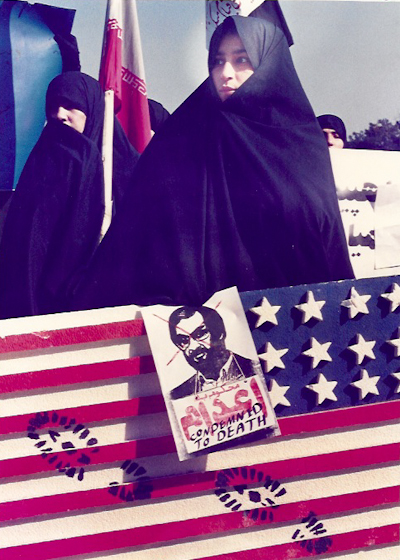

The name Salman Rushdie vaguely registered with me, but I had no clue in what context. As we neared the center of Tehran we could see crowds of mostly women dressed in black making their way in the same direction. We parked the car and followed them until we ran into a parade where women were holding up, “Death to Salman Rushdie” signs and the obvious placards which read, “Death to America.” In retrospect, there was really nothing spectacular about the march and I hardly consider the photographs that I took to be anything special. Regardless, I treated it like any other news story and ran around with my camera trying to cover all the angles. The only unique thing about this demonstration was there was no foreign press presence at the event other than myself.

At the time, I had no idea of the magnitude of the story or the response it would have across the globe. To me, it seemed like every other government-sponsored demonstration directed against the West.

Once the demonstration was over, my friend drove me back to my hotel so I could pack my belongings and then he took me to the airport. When I got to Dubai, I dropped off his film at a courier service and then proceeded to develop my own film and transmit the photos to my news agency.

The following day, I received an unexpected call from the chief photo editor who congratulated me for a job well done. He said that my pictures made the front page of countless newspapers around the world with numerous publications running full-page photo essays.

After being at the center of attention that “The Satanic Verses” generated, I wanted to learn a bit more about the author. However, at that time there was no Internet and I couldn’t go down to the local library and check out one of his books. There was really no option other than to ask one of my colleagues, but that also seemed a little embarrassing because having just returned from Tehran I should have been the one who knew thing or two about the story. In the end, I just let it go.

Not long after I returned from Tehran, I was laying down on my couch watching television, when I noticed a book sticking out from beneath a stack of old newspapers. I reached over to see what it was, and when I pulled it out, I noticed it was copy of “The Jaguar Smile” — a book that Rushdie wrote after he visited Nicaragua.

It turned out to be a book sent to me by a friend but because I found it boring, I never finish it. However, having just been surrounded by people calling for the Rushdie’s head, I decided to try and have another go at it. My second attempt also ended in failure. Later, when I had the opportunity, I picked up a copy of “The Satanic Verses,” but I had the same reaction; it was not my cup of tea. This is not to say that Rushdie is a bad writer; actually, he could be the greatest writer, but his style does not appeal to me.

If Khomeini had not issued a fatwa against Salman Rushdie I — like many others — would never have attempted to read “The Satanic Verses.” Like most news stories, the Salman Rushdie affair eventually disappeared from the headlines. However, its relevance still remains very much alive. The recent uproar over the “Innocence of Muslims” is the latest proof.

There will always be controversial works of literature or art, some which are worthy and others worthless. Now, that we live in a world where nearly everyone has access to the Internet and can witness events in real time, a new set of ethics has to take shape to prevent cyber provocations from spinning out of control. This can only happen through mutual respects of culture, tradition and values.