(MintPress) – For the first time in decades, a new president is giving hope for the future of Somalia — at least for some.

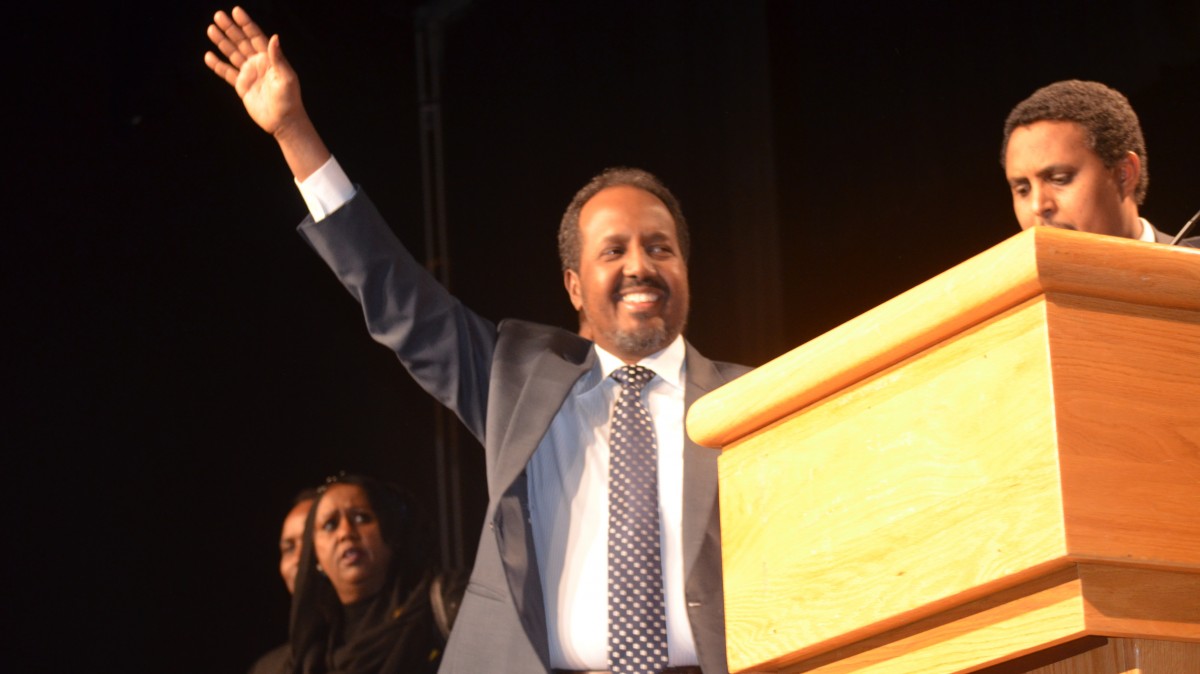

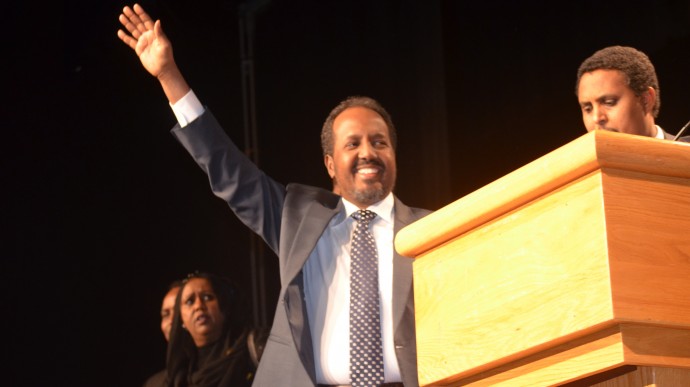

The energy was electric inside the Minneapolis, Minn. Convention Center Friday night, as the Somali community awaited the arrival of newly elected President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, the representative of the first Somali government to be recognized by the United States since militants toppled former dictator Mohamed Siad Barre in 1991.

Prior to America’s pull of support for Somalia in 1991, it had supported Barre’s dictatorship — one that was friendly to outside business. U.S. corporations benefited from oil in the region, but left 4.5 million Somalis facing food shortages. Famine took the lives of 3,000 people during his reign. Before the overthrow, the U.S. began to pull out. Yet when Barre was tossed from power, the U.S. retreated altogether.

In 1993, relations were severed even deeper when militants shot down two U.S. helicopters, killing 18 Americans in an incident most commonly referred to as Black Hawk Down.

Now, a new alliance between the U.S. and Somalia has been made.

Mohamud’s visit to Minnesota, home to the largest Somali population in the U.S., came just one day after meeting with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and President Barack Obama. The meeting proved historic, as the U.S. has long refused to support the nation’s governments throughout the years, citing widespread corruption, civil war and terrorist breeding.

Minnesota Congressman Keith Ellison, a Democrat, told the crowd of more than 3,000 that in order for stability to be gained, the constant support of the Somali population on government officials is needed.

“We are depending on you to call on the American government to give the government full assistance,” he said.

But what does that U.S. government support mean for Somalia?

An improved economy?

The U.S. acknowledgment opened the doors for Somalia to receive funding from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) — resources that are said to be intended for uses that would benefit Somalia’s economy — mainly Mogadishu’s — in the long run. It also opens the doors for multinational corporations to build infrastructure and benefit from resources in the region all over again.

In his speech Friday, President Mohamud promised an improved economy — a comment that drew praise from the audience.

The government is going to do so through a variety of avenues, including the optimization of business related to coal, oil, livestock and fishery. Somalia is considered home to a relatively untapped oil resource. While other areas of Eastern Africa have been touted for oil-rich land, Somalia’s war torn countryside has largely put up a roadblock for extraction.

Two decades ago, Conoco-Phillips and Shell Oil led the oil rush in Somalia, but withdrew amid instability. Now, the Somali government is saying it’s hoping to once again be open for business, actively changing its laws in favor of multinational corporations.

“Given that the security condition of the country is improving at a rapid speed and the presence of legitimate transparent government, companies of the past and the new ones are all welcome,” the Somali Minister of Resources told Mareeg news agency in December 2012. “Somalia will be open for business sometime in 2013 and we honour the agreements of the companies who filed ‘force majeure’ and left the country due to the civil war. We are now working to review the Petroleum Law and make it more competitive and attractive to oil companies and investors.”

While the U.S. is just now recognizing Mohamud and his government, foreign aid to the region hasn’t ceased in recent decades. In the last four years, the U.S. has spent $1 billion in anti-terrorism efforts, mostly through the African Military Coalition. It’s all helped lead to this.

Opposition

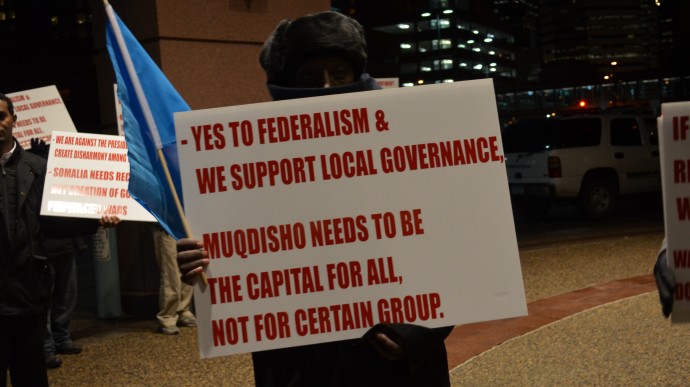

A group of protesters gathered Friday outside the Minneapolis Convention Center. Hours before the president’s visit, demonstrators told MintPress News they were concerned that economic benefits would only be given to loyalists of the president.

Clans located outside of Mogadishu would be left out of the puzzle, without proper governance to deal with the threats posed by al-Shabab. Mogadishu may be better off, but those living in more rural areas will continue to be ignored.

“We don’t want to go back to clan-based wars,” Abdi Fatah Ahmed, a native Somali who lives in Minneapolis, told MintPress News. “We don’t trust him in that. He looks out for his own people. It’s not fair, and we want the world to know this.”

Ahmed and other protesters weren’t opposed to U.S. recognition of Somalia, but worried that it would lead to a deepened sense of entitlement for those living in Mogadishu, leaving those in the outskirts, particularly the southern region of Kismayo, to fight against al-Shabab themselves.

Protesters held signs demanding local political control, showing concern that President Mahmoud appointed his own representatives — rather than the peoples’. They claimed the president wasn’t following the constitution, which promotes federalism. They worry the freedom celebrated by Somalis inside the Minneapolis Convention Center Friday would not be awarded unilaterally throughout the nation.

Kismayo has long lobbied for independence from the Somali government, which now will not likely be achieved, as the new government is asserting political control over the area.

Kismayo, independence, coal and terrorism

An anti-terrorism training site was set up by the CIA in the outskirts of Mogadishu, complete with a compound guarded by Somali soldiers but under CIA operation. Its target is largely centered around the southern region of Kismayo.

In 2011, the Nation published an expose on the CIA’s presence in Somalia, highlighting a secret prison built beneath the grounds of Somalia’s National Security headquarters. Its counterterrorism efforts expanded beyond the prison to include widespread surveillance and drone strikes in areas overrun by al-Shabab.

The lifeblood of al-Shabab, economically speaking, lies primarily in Kismayo’s coal industry. Extremists, having taken over Kismayo, generated more than $11 million in revenue through exports and taxes in 2011, according to a United Nations report. Its customers? Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Extremists in Somalia have long fought to create a Taliban-like, Islamist state in Somalia, using their religious extremism to justify torture, beatings, suicide bombings and executions. As of 2009, al-Shabab’s numbers reached 7,000, all of whom are funded from the profits gained by the organization through control of port cities, including Kismayo.

Where did this extremist ideology come from? Abdul Ghelleh, writing for Wardheer News, says Saudi Arabia influenced the ideological climate, moving into the area after the 1991 collapse.

“When the Somali state collapsed in 1991, the government’s social management institution — for cultural and religious guidance — which controlled what’s permissible in the country and what’s not — went with it,” he writes. “And with the lack of border controls following immediately the collapse of the Somali state, numerous foreign Islamic ideologies were imported into the country. the biggest and most effective of all, was Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi Islam (recently upgraded to Salafism) which was not traditionally practiced by the African societies. It found a fertile ground in the vacuum that followed the overthrow of the Siyad Barre’s military government.”

Somali extremists are also connected to al-Qaida, providing a partnership and opportunity for training, strengthening al-Shabab’s control in Somalia.

The future of that very industry hangs in limbo as the new government takes over. The question is: Who will benefit from the coal? While removing it as a life source for al-Shabab isn’t contested by the people of Kismayo, there’s concern that funding will benefit Mogadishu.

“For the moment, there’s no reason for there to be a fight over charcoal,” a Nairobi-based Somali expert told the Daily Beast, while also indicating that it could set off a political firestorm. “If the central government remains adamant and tries to impose its will without a negotiated settlement, then in the context of the broader Jubba Valley issue, it’s just one more irritant to divide the two sides.”

The US, African special forces war

The U.S. approach to dealing with rising terrorism in Africa has not exactly been hidden — at least the general picture. In a speech given in 2012, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta laid out the new counterterrorism strategy in the content, in which he described an increase in Special Operation Forces (SOF) activity, drone strikes and surveillance — all of which have been used in Somalia.

“ … To truly protect America, we must sustain and in some areas deepen our engagement in the world — our military, intelligence, diplomatic and development efforts are key to doing that,” Panetta said in a speech given at the Center for New American Security.

Special Forces are expected to increase to a 72,000 on-the-ground presence by 2017. This new agreement with Somalia could just allow the U.S. to inch closer to this goal. The question now is whether the operation will be effective in ending the extremism little by little through force, or if such force will only breed more resentment and the cycle of political instability that has constantly inflicted the majority of the continent.