Much has been made in energy industry circles this past month of a report released by the Paris-based International Energy Agency that suggests the United States may soon overtake Saudi Arabia and Russia as the world’s premier oil-producing country. While U.S. oil production has increased of late, the fundamental fact remains that fossil fuel-based energy security will never again be within America’s grasp. To comprehend why, one has to understand the economic dynamics at work in the oil industry, the geological reality of shale and tar sand oil production and trends at work in the global economy.

In their report, “World Energy Outlook 2012,” IEA analysts argue that the shale oil revolution taking place in the United States has fundamentally transformed U.S. energy production for the better. It will, in short, reverse the decades-long decline in U.S. domestic oil production and significantly reduce, if not eliminate altogether, U.S. dependence on foreign oil.

In a previous column, I described the new technology behind this domestic energy revolution:

“Hydraulic fracturing, or ‘fracking,’ is a testament to human ingenuity and the lengths to which corporate America will go to feed our addition to oil and gas. In short, fracking consists of injecting, at extremely high pressures, a witch’s brew of chemical fluids in oil- and gas-bearing rock formations. The combination of chemicals and pressure breaks open the rock, freeing the trapped oil and gas and allowing the precious hydrocarbon resources to be recovered for human use.”

Interestingly enough, this technological revolution was made possible by government research and development efforts, and its implementation is now made possible by the historically high prices for conventional oil we see today. While the tale of yet another free-market revolution brought to you by those Bolsheviks in Washington is entertaining enough, the real story behind the rise of this new technology is indeed the high prices cited by oil industry. However, what they neglect to mention is that the economic sustainability of this new technology is premised on continued heavy declines in production from traditionally cheap sources of oil. This is not good news, and it calls fundamentally into question the IEA’s panglossian predictions.

This is because fossil fuels are by their nature finite resources, appearing only after organic matter is cooked underground by the Earth’s pressure over long lengths of geologic time. Depending upon the cook time and the exact geologic conditions encountered, sometimes the carbon in this organic matter turns into liquid petroleum of the type that spurts to the surface when drill pipes breach oil-bearing rock formations. This is not a sea of oil as popularly imagined, however. Instead, the release in pressure created by the bore hole allows microscopic droplets of trapped oil to flow and be recovered.

Oil’s past will not repeat itself

During the 20th century, all the oil in convenient locations that took very little effort to recover was discovered and developed. The names of the so-called “elephant” fields that were discovered during this era are legends in the oil industry. Fields like the one in East Texas, which produced the Spindletop gusher in 1901, or the truly massive Ghawar field eastern Saudi Arabia, which has accounted for most of the oil produced by that country since 1948, transformed entire societies and changed the course of human civilization.

Today, though, these fields are now decades old and have either long since slid (East Texas) or are about to slide (Saudi Arabia) into irreversible production declines. Globally, humanity has not discovered more sources of conventional oil than we, as a civilization, have produced and consumed since the 1980s. Thus, the cheap, plentiful oil that was so easy to recover that one could discover it while out shooting at some food à la “The Beverly Hillbillies” no longer exists.

What has replaced it is costly, heavy petroleum that needs much more refining effort to make useful, or traditional deposits found at the edges of human habitability and reach such as those in the deep ocean or the Arctic wastes. Other sources of oil have also been found in the form of tar sands and shale oil, which, as noted above, is the product of technological innovation. The great hope of the oil industry is that production from these new sources will replace the fields discovered and developed during oil’s golden age in the 20th century.

Unfortunately, this is not likely to happen in a way that meaningfully improves prices for U.S. consumers – though producers will certainly get rich. First, the infrastructure required to get truly large amounts of tar sand oil to market, like that which is found in Canada, is staggering and is orders of magnitude more complex and expensive than that for traditional sources.

Tar sand is essentially oil that is not fully “cooked” and so resembles coal more than traditional petroleum. As such it is literally mined, not pumped, from the Earth and the environmental devastation associated with it is, naturally, quite high. Once extracted, the tar is heated up, usually with natural gas though some have proposed using nuclear power, and combined with local sources of water in order to release the hydrocarbons into a liquid form capable of being refined further. It is, to say the least, hideously expensive, filthy and grossly inefficient in terms of net energy gain.

The supply of oil

While Canadian production of tar sands has increased, the real miracle the domestic oil industry is betting its future on is the shale oil released from the fracking process described above. Shale rock, unlike traditional oil deposits, is geologically much “tighter” rock to recover oil from – else it would not require fracking – and one shale oil well, once fracked, produces far less oil for far less time than is the case for a traditional well. This makes eminent sense. If oil is locked up in tighter rock, less will be extracted from any single producing well because less oil is capable of flowing to the wellhead than is normally the case.

This is clear to anyone familiar with production data coming out of shale fields like the Bakken field in North Dakota. As demonstrated in an analysis of open-source data by industry skeptics at the popular Peak Oil blog “The Oil Drum,” shale oil production from a single well does indeed spike, but after a brief, highly lucrative period as a quasi-gusher production plummets. Within three years, on average, these sources of new oil are effectively tapped out. Indeed, there is a great irony here as the traditional fields that shale oil is supposed to replace will continue to produce oil, albeit at increasingly reduced rates, far after shale wells that are being brought into production today are tapped out and abandoned.

What this means is that for shale oil to meaningfully replace traditional production in an economic sense – let alone for the U.S. to go from a net oil importer to a net exporter and so replace Saudi Arabia as king of the oil hill as the IEA predicts – there needs to be massive, sustained, ever-increasing investments into shale oil production. This is so because flow rates of oil from real, existing, producing wells is ultimately more important to the economy than the theoretical amount of oil companies, government agencies and the IEA say is capable of being extracted.

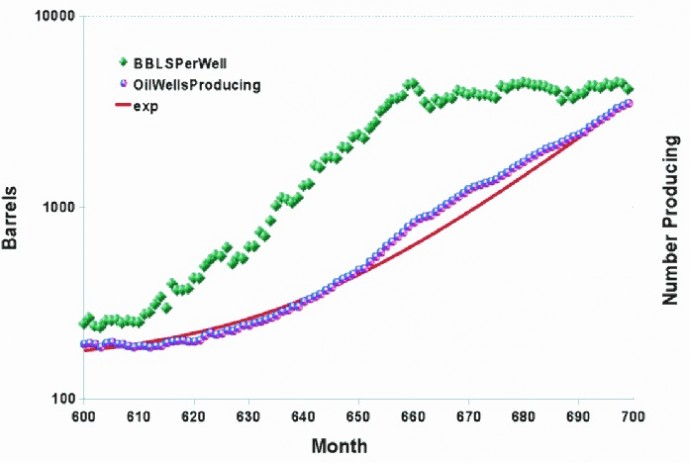

And this, mind you, is merely to remain where we are today. If, as expected, traditional oil sources continue to decline, the so-called Red Queen effect – where we run faster and faster to stay in place – will become worse by many orders of magnitude. Indeed, we can already see hints of that in North Dakota (see chart below), where, despite more wells being brought into production, total oil produced per well has actually flattened – largely due to the “peak and plummet” phenomenon noted above.

Bakken Oil Production, BBLs/Well. Courtesy of TheOilDrum.com

So, on the production end, the IEA prediction is premised on traditional oil sources only marginally declining from current rates while, at the same time, unprecedented amounts of industrial infrastructure and financial capital is expected to be deployed to develop our shale oil resources. This could happen in a way the IEA expects, but a realistic assessment of existing traditional oil production decline rates, the likelihood of bottlenecks and delays in the rollout of shale oil production infrastructure and the staggering reality of quickly diminishing production from shale oil wells suggests this will be extraordinarily difficult to pull off. There is indeed a LOT of shale oil out there – probably as much as traditional oil if not more so. The unfortunately reality is that it takes Herculean efforts to recover economically in the amounts we are used to consuming.

Shale oil demand

If the supply side story inherent in the IEA’s optimistic assessment of shale oil production is flawed, what about the demand side? In the developed world the signs are good that oil consumption will continue to decline even after the recession has ended. Energy-hungry heavy industry has been offshored while car ownership among American youth has in many ways lost its appeal. Additionally, more efficient cars, like the Toyota Prius, are beginning to make inroads with American consumers.

Indeed, the IEA’s own chief economist, Fatih Birol, has stated that his organization’s rosy predictions of American energy independence is at least in part based on expectations that the United States will continue to see improvements in fuel and energy efficiency of the type seen over the past decade. Whether this will continue without a strong price signal coming from the oil markets or the government remains to be seen. History shows, however, that when energy prices plummeted in the late 1980s and government will to improve efficiency standards wavered, automakers returned to making highly profitable gas-guzzlers and American efficiency standards stagnated and declined as a result.

American consumers, however, are not likely to be the determiners of future oil prices for much longer regardless of what they do. That is because increasing demand for energy in China, India and the Middle East is expected to increase by 35 percent-46 percent by 2035. This means that even if the “developed” world increasingly weans itself off oil through continued improvements in energy efficiency, the loss of demand from Western consumers will be more than made up by increased demand from newly prosperous consumers – numbering in the hundreds of millions – throughout Asia.

This expectation coincidentally explains much of the current push by American oil companies to complete the Keystone oil pipeline and reveals more fully the long “energy security” con being pulled by the industry.

Keystone pipeline

The pipeline, which will connect landlocked shale and tar sand oil in Canada, the northern Great Plains and the American West, with refining and export facilities along the Gulf of Mexico, will allow producers in places like North Dakota’s Bakken field to finally sell their oil on the global markets. Given that the global price of oil has been consistently higher than the American price by anywhere from $10 to $20 a barrel for several years now, this represents a potential profits bonanza for American producers.

While this is good for global consumers, who will benefit from lower prices stemming from increased American production coming to market, American consumers will suffer as the domestic price for oil increases as American supply meets global demand. Increased U.S. production, in other words, will mean bigger profits for big oil and cheaper oil for China and India, but no real savings for American oil consumers.

Indeed, if energy security, not bigger profits for big oil, was the goal of the American government, then the Keystone pipeline would not be allowed to proceed. Instead, incentives would be put in place to shift refining capacity closer to the landlocked North American shale oil fields or otherwise direct pipelines from places like North Dakota’s Bakken fields to major American population and industrial centers in the Midwest, Northeast and the Pacific Coast – not export facilities along the Gulf Coast.

So, the news coming from the IEA, while noteworthy, should be taken with more than a bit of a grain of salt. The U.S. could become the next Saudi Arabia, sure, and President Obama could win another Nobel Peace Prize after flying to the moon under his own power, too. Santa Claus could also appear in front of you with a magic sack full of a never-ending supply of toys and treats. Most of us stopped believing in St. Nick a long time ago, though, and if you believe what an oil industry executive has to say about industry developments being good for consumers … well, then I have a storm-lashed bridge in Brooklyn to sell you.