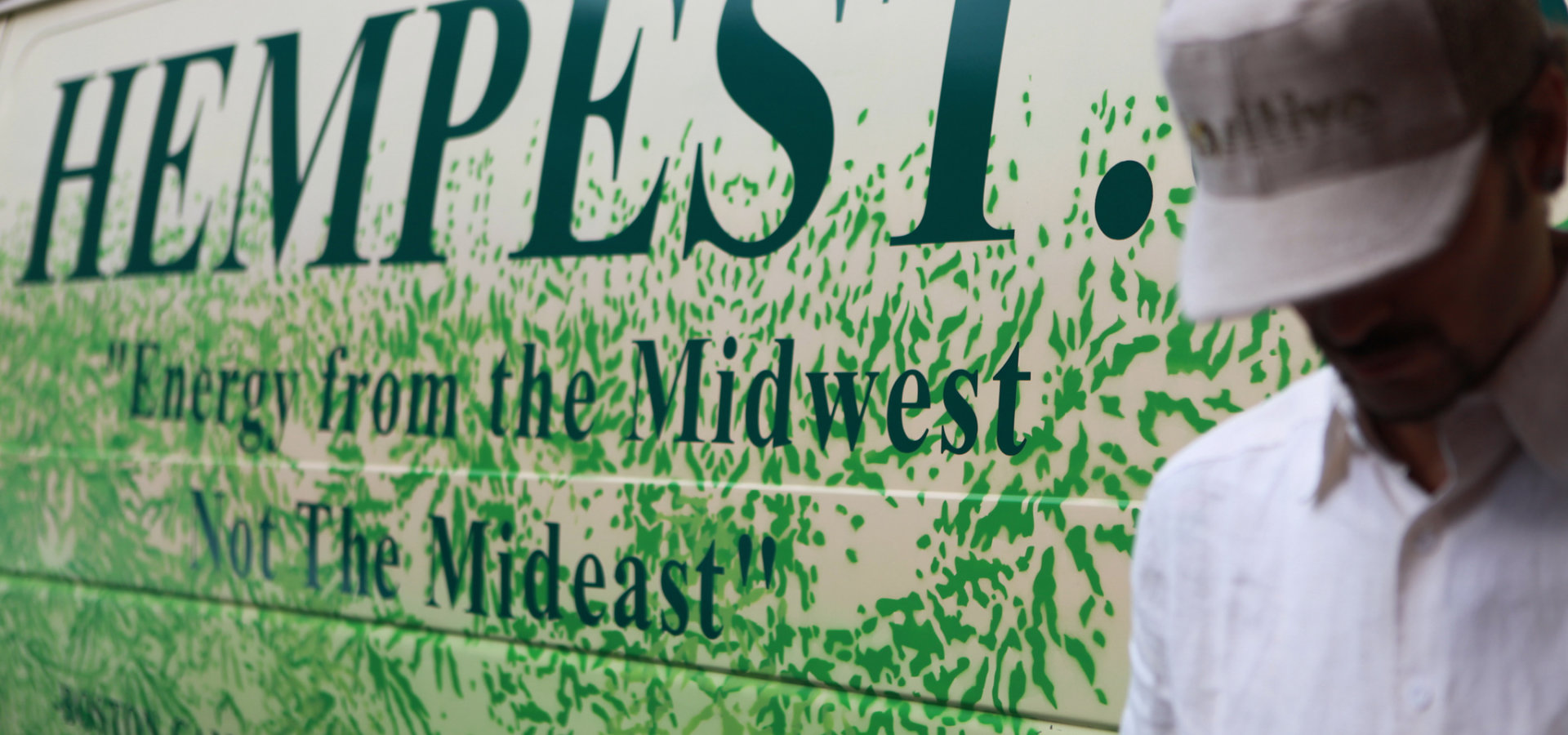

The Hempest van, which runs on vegetable oil, diesel, biodiesel or hemp oil. (Kim Napoli, Hempest Inc.)

BOSTON — Jon Napoli jokes that when he opened a small shop specializing in hemp products in 1995, it was because, at 23, he just didn’t have anything better to do.

But that’s not quite the whole story.

“Ending the prohibition on hemp and cannabis was something I needed to be involved in,” he tells MintPress News. “And I figured I could do it economically.”

“Money turns the world around, and social change can come through private enterprise,” he continues, explaining that he wanted to show people, farmers and politicians that there was a lot of money to be made in the hemp industry.

According to the Hemp Industries Association, a nonprofit trade association, the value of hemp retail products sold in the United States last year exceeded $581 million, up from $500 million in 2012. That’s no small feat for an industry that largely relies on imported raw materials and finished products because of a long-standing prohibition on its major resource — hemp.

Under the federal Controlled Substances Act, cannabis is prohibited in all forms because marijuana, a plant in the cannabis family, has psychoactive properties. While hemp is also in the cannabis family, it is not a drug and contains virtually no THC — the psychoactive component in marijuana that gets people “high.” Some states have moved to legalize marijuana either for medicinal or recreational purposes, or both, or to decriminalize possession of the drug, but it remains illegal at the federal level. Likewise, since 1970 it has been illegal to cultivate hemp in the U.S. without a federal permit.

The federal 2014 Farm Bill, however, prevents federal agencies from interfering with state-designated projects for industrial hemp research and development. So far, 19 states have laws to provide for hemp pilot studies, production, or both, as stipulated by the Farm Bill.

Napoli says the bill — recently passed as part of the federal government’s $1.1 trillion spending bill — is a “great first step” toward the U.S. being able to re-establish its relationship with the versatile plant. Practically every part of the plant can be used and substituted for other ingredients or components — and it has been for centuries: Christopher Columbus used hemp sails and rope when he traveled to America in 1492. Founding fathers including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson grew lucrative hemp crops. Until the invention of the cotton gin in the 1820s, hemp was the fiber of choice for textiles. Fiber from the hemp plant useful in producing strong, durable fabrics that have antimicrobial and anti-mildew properties, according to the North American Industrial Hemp Council, which makes it ideal for all manner of clothing — including pants, dresses, underwear and socks.

The fiber isn’t the only useful part of the plant, as hemp crops are also harvested for seeds, seed meal and seed oil. Hemp seeds are a rich source of digestible protein and can be used in a variety of ways, like in baked goods or any other dish or snack that would benefit from the nutty-flavored, healthful component. As with as almonds and soy, hemp seeds can be used to make non-dairy versions of products like milk and cheese.

Oil extracted from hemp seeds can be used in the place of any other oil in everything from cooking to powering a car. The Hempest’s Ford van has a diesel engine, and like all diesel engines, it can easily be converted to run on vegetable oil, which the Hempest procures from restaurants and filters before putting it in the gas tank. Since hemp oil must be imported, it’s too expensive to use to run the van, but Napoli says it’s still a great educational tool for the wide range of uses for hemp, as well as the power, reliability and affordability of alternative energy sources.

“It lets people know that there are alternatives to burning fossil fuels,” he says. “The answers have always been there; we’ve just been held captive by industrial interests.”

The Hempest store on Boston’s Newbury Street. (Kim Napoli, Hempest Inc.)

Positive consumption

Over the past 19 years, Napoli’s business, the Hempest, has gone from peddling hemp hats and greeting cards out of a small shop on Huntington Avenue to selling high-end merchandise from producers around the world, as well as its own line of apparel and accessories, out of a growing retail presence on Boston’s swish shopping destination, Newbury Street, and online.

The relocation was made possible when Napoli’s childhood friend, Mitch Rosenfield, jumped on board. After college, Rosenfield was working, living with his mom, and saving up money. His dad had died of cancer a few years earlier, so he was on a kick of working toward leading a healthier lifestyle, eating more natural foods, and looking for ways to leave a positive impact on the world by making consumption a more positive part of life.

When a retail spot opened up on Newbury Street, the duo pooled their resources and took the plunge.

“Jon had $15,000 in inventory. I had $15,000 in the bank,” Rosenfield says, explaining that after paying first and last months’ rent and leaving a security deposit, they had about $3,000 left to sink into the business. For the next couple of years, every dollar the Hempest made went toward buying more hemp products to sell, and as Rosenfield says, “That was the whole philosophy anyway: Buy hemp.”

The shop on Newbury Street smells of nag champa, patchouli and wood, which wafts out onto the sidewalk, mingling with an eclectic mix of music pumping from outdoor speakers. By putting a hemp store on the same street as high-end restaurants and top-tier stores like Chanel and Louis Vuitton, as well as global brand behemoths like Nike and Adidas, Napoli and Rosenfield were hoping to change hemp’s image.

“We didn’t sell tie-dyed clothes, wouldn’t play the Grateful Dead for the longest time,” Napoli says. “We wanted to combat the stereotype.”

There’s no particular Hempest “customer.” Napoli says that their clientele is mostly men, aged 20-40, but really, “the Hempest customer” is anyone who is interested in supporting independent business and buying eco-friendly, high-quality products.

Napoli admits that it’s still a niche market, but having the location on Newbury Street has made it seem like “just another clothing store.” And more importantly, it’s provided the pro-cannabis duo with a platform for educating the public on hemp’s unique benefits and dispelling myths and stigmas surrounding the plant.

“The ‘Can I smoke my shirt?’ thing has definitely tapered off,” Napoli says. “It’s just become more accepted — as it should be.”

Rosenfield agrees, “Thankfully, we really don’t hear that too often anymore.”

At the beginning, he says, the Hempest was peddling a product closely associated with marijuana, at a time when marijuana was far less accepted by the general public than it is today. “We were toeing the line between marijuana and retail, but now people hear about medical marijuana and recreational marijuana, and hemp is just no big deal,” Rosenfield says.

Napoli and Rosenfield say they still find themselves explaining the benefits of hemp and the differences between hemp and marijuana.

“In terms of the food items, do people know it’s the best source of vegetable protein and essential fatty acids? No. Do they know it’s good for them? Yes. There’s generally an understanding that it’s a healthy plant for people and the Earth,” he explains, noting that he’s sure there’s a lot of confusion about how wheat or soy is grown, too.

For Rosenfield, these opportunities to educate the public are the best part of his job.

“I’ve talked to people for countless reports and school papers on hemp. I can’t tell you how many high school and college kids I’ve helped, and I can’t even tell you how much I love that — that part when someone wants to listen,” Rosenfield says.

Positive momentum

Since about 2003, the Hempest has been focusing on creating its own line of clothing, which is produced in an ethically-run factory that they have visited themselves in China, and bolstering its online presence. They produce small batches of clothing, in styles and colors they think their customer base will like, which keeps margins high and the chances of over-stocking low.

Products from the Hempest get shipped across the country and around the world every day, especially during the busy Christmas shopping season. Rosenfield says they regularly ship orders to Europe, Japan, South America, “and I send stuff back to China sometimes, if we get an order from there.”

Going forward, Napoli and Rosenfield agree that the “brick and mortar” aspect of the Hempest may not be around forever (though other locations have opened up across the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts; Northampton, Massachusetts; and Burlington, Vermont). Napoli is quick to note that one day he’s going to “get sick of paying rent,” and they both say that wholesale and web business are the most obvious avenues for growth.

Yet with the amendment to the Farm Bill that’s slowly paving the way for the U.S. to cultivate hemp for research and industrial purposes in those states where it’s legal, it seems like there’s only growth ahead for the U.S. hemp industry, which hopefully will include the Hempest for years to come.

“We have to import clothes from China, food from Canada. Taxes, customs, tariffs… it all adds up. And why should we be sending money over there?” Napoli says, noting that the Farm Bill is a huge first step toward the wide-scale production of hemp, an environmentally sound, sustainable crop.

It’ll be some time before the U.S. catches up with hemp producers like China or Canada — Rosenfield says the U.S. is “millennia” behind the Chinese, but the U.S. was home to the world’s largest hemp industry up until the early 1900s. With enough supportive legislation, research, time and money, the founders of the Hempest don’t see any reason why that industry won’t bounce back to it’s pre-prohibition stature.

“Hopefully we’ll see hemp crops growing along the side of the highways the way we see corn in 10 to 15 years,” Napoli says.