Imagine standing at a TSA security checkpoint on your way home for the holidays. You’re getting ready to go through the awkward travel procedures instituted almost immediately after 9/11 when the Transportation and Security Administration (TSA) was created and air travel in the United States morphed into a search and seizure operation with the implied possibility of your detention and interrogation.

The initial outrage such expressions of implicit state violence caused early on eventually gave way to begrudging acceptance. But now, a new layer of “security,” that could restrict freedom of movement even further, is being rolled out at several ports of entry in partnership with health technology industry leaders, academic institutions, and government health entities in more than three dozen countries.

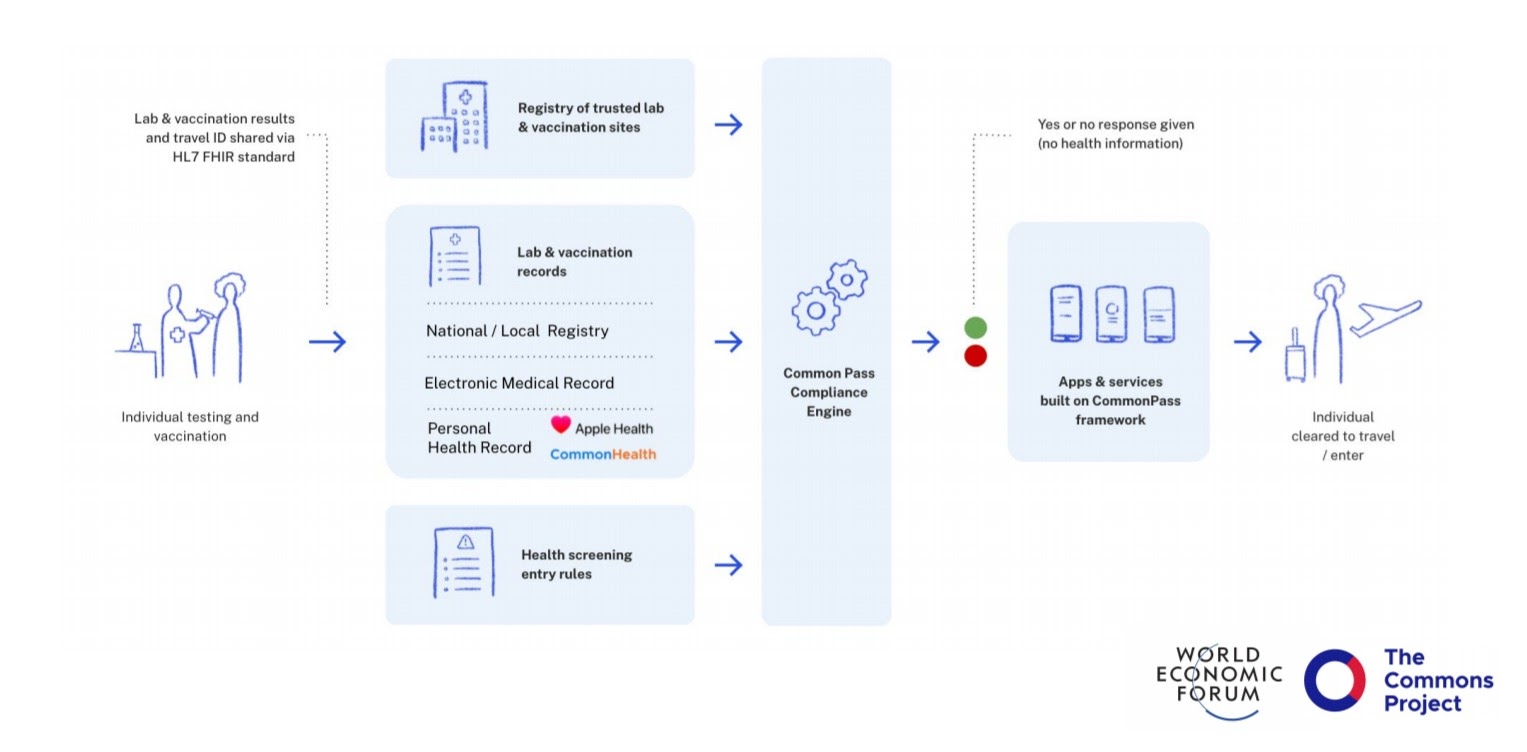

A new digital certificate called CommonPass, designed to serve as a clearance mechanism for passengers based on a health diagnosis underwent its first transatlantic test on October 21 under the watchful eye of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) at Heathrow Airport in London. There, a group of select participants embarked on United flight 15 to Newark, New Jersey after being screened and tested for COVID-19 at the point of departure in a largely ceremonial exercise that included initiative co-founders, Paul Meyer and Bradley Perkins.

The app’s first trial run took place with much less media fanfare last month on a Cathay Pacific Airways flight from Hong Kong to Singapore and marked the beginning of the CommonPass pilot project launched by The Commons Project non-profit organization in-tandem with the World Economic Forum.

Travel industry insiders claim that CommonPass will allow international travel to resume before a COVID-19 vaccine is made widely available by applying standard methods for certification of lab results and vaccination records of travelers through the CommonPass Framework, based on criteria set by the governments of each port of entry.

J.D. O’Hara, CEO of one of the world’s largest travel services companies and one of the participants at Wednesday’s CommonPass trial run, hailed the app’s ability to “verify health

information in a secure, verified manner,” while Roger Dow of the U.S. Travel Association released a statement praising it for paving a “way forward” for the global economy in the wake of the pandemic.

As the multi-sector, global response to the coronavirus tightens the noose around civil liberties, CommonPass stands out as one of the most appalling and dangerous attacks on basic human rights in the name of public health and is rife with a potential for abuse so great, that it behooves us to find out more about the people and interests behind it.

Feudal revivalists

In medieval times, the ‘commons’ denoted the de facto and collective ownership of land, which peasants used to plow, sow and harvest or raise sheep and cattle. The rise of the land-owning classes in post-Magna Carta Europe, and England in particular, slowly eviscerated this form of communal privilege through the enclosure system, which redistributed the commons to the proto-capitalist class in partnership with the monarchies and create the system of oppressive labor exploitation known as feudalism.

Starting in 1604, the Enclosure Acts of England created legal property rights for land that had belonged to the farmers and shepherds, forming the basis of modern-day capitalism. Today, that scene is being repeated as the Internet, an information ‘commons’ is being carved out by Big Tech and led by organizations like The Commons Project, which avails itself of a name that connotes the total opposite of its purpose.

Co-founders Paul Meyer and Bradley Perkins are the non-profit’s CEO and Chief Medical Officer, respectively. Perkins began his career over thirty years ago at the Center for Disease Control and, for nearly a decade, worked at the RAND corporation’s health care policy division, RAND Health Advisory Board. Meyer, for his part, is a Yale law school graduate, who was writing President Clinton’s speeches years before receiving his graduation diploma from the storied institution. Both have extensive career histories in the fields of health and technology, though in very different areas and with strange bedfellows along the way.

In 2009, Perkins became the Chief Technology Officer for a publicly-traded cross-national operator of hospitals and clinics called Vanguard Health Systems. Vanguard had been established with funding from Morgan Stanley and controlled by the Blackstone Group since 2004, maintaining control all though the company’s IPO in 2011. Two years later, Vanguard was acquired by Tenet Healthcare, creating the third-largest investor-owned hospital company in the United States with a total of 65 hospitals nationwide and over 500 healthcare facilities.

Besides being one of the biggest healthcare companies in the United States, Tenet is also one of the most notoriously corrupt. The same year it bought Vanguard, it was slapped with a major whistleblower complaint that disclosed the company’s fraudulent practices. That lawsuit resulted in a $514 million settlement. A more recent case involving a conspiracy between Oklahoma orthopedic surgeons at one of its facilities was settled for $66 million in 2019. But, Tenet’s problems go back even further to the early 2000s when fraud and performing unneeded surgeries led to a multitude of lawsuits and even a Senate investigation.

The Vanguard deal marked the end of Perkins’ tenure there, who chose to take a $1.9 million package instead of joining the newly merged conglomerate like its CEO and much of its staff did. He would move on to create a company of his own called Sapiens Data Science; a health tech platform that provides access to “credible scientifically validated data algorithms” and looks to create a “new revolutionary health ecosystem.”

Meyer’s background is more complicated, and his arrival on the healthcare scene runs through different channels linked to American intelligence cover operations dating back to NATO’s war in Kosovo and the former Yugoslavia during the early Clinton years. It is his involvement with an infamous human-trafficking outfit known as the International Rescue Committee or IRC, that should be cause for concern given his role in The Commons Project and flagship CommonPass app.

The Meyer of Kosovo

Before he was named Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum or Henry Crown Fellow at the Aspen Institute, and even before becoming a Term Member of the Council on Foreign Relations and receiving MIT’s 2003 Humanitarian of the Year award, Paul Meyer found himself in war-torn Kosovo installing a new Internet infrastructure system to replace the one destroyed in the war, only days after NATO bombs had stopped shelling the Serbian people.

Barely out of law school and having spent two years writing President Clinton’s speeches as the conflict in the former Yugoslavia was transpiring, Meyer was tapped by the IRC to lead a UN and private relief effort called the Internet Projekti Kosova (IPKO) or Kosovo Internet Project, with tech-savvy local Akan Ismaili to handle the complex technical issues and Teresa Crawford from the Advocacy Project to “uplink” satellites in the region with the stated purpose of reuniting displaced Albanian families. The system was set up atop a building used by the British KFOR Civil-Military Cooperation CIMIC and British Royal Engineers were also brought onto the project, among others.

Eventually, the IRC gave the project to a non-profit organization “dedicated to providing wide access to the Internet in Kosovo.” IPKO is today the largest telecom, internet, and cable TV company in Kosovo. Meyer remains involved through the IPKO Foundation, which he co-founded to provide “free technology education” to Kosovar students.

By the 1950s, the IRC was known to be an “integral link” in the CIA’s covert network led by Tony Blair protégé and former British Foreign Minister, David Miliband since 2013. In 2018, the IRC was embroiled in a child-sex trafficking scandal dubbed the “sex-for-food scandal” covered extensively by Whitney Webb in a recent article. The organization’s cover-up of dozens of sex abuse, bribery and fraud allegations resulted in the U.K. government withdrawing its funding from the organizations. However, no IRC employees were prosecuted over the 37 incidents detailed in the report.

Currently, the IRC is very involved in the implementation of a biometric ID system for refugees of the ongoing conflict in Myanmar, a project funded by the Rockefeller Foundation-backed ID2020 Alliance, which also funds The Commons Project. IRC’s Mae La initiative, however, receives most of its funding through the notorious CIA-cutout USAID and intends to create a “blockchain-based digital identification” system using iris recognition technology to give refugees access to IRC’s services in Thailand. Long term goals include rolling health, work and financial data together into a single ID system, that will determine access to food, healthcare and mobility.

We want your DNA

The difference between IRC’s Mae La project and The Commons Project is a question of class. Class status, to be specific. But, it is essentially the same idea and covers the same interests of the groups and individuals who form part of the Commons Project’s board of trustees; many of whom have been part of the digital tracking and healthcare technology space for years.

People like Linda Dillman, who ran Wal-Mart’s implementation of RFID employee tracking technology as the retail giant’s CIO or the former Chief Technology Officer for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bryan Sivak, who is now a Managing Director at Managing Director at Kaiser Permanente, one of the largest healthcare insurance plan providers in the nation. Other trustee affiliations stand out, as well, such as Will Fitzpatrick, General Counsel to the Omidyar Network and George W. Bush’s Assistant Secretary of Defense, Health Affairs, Dr. William Winkenwerder, Jr.

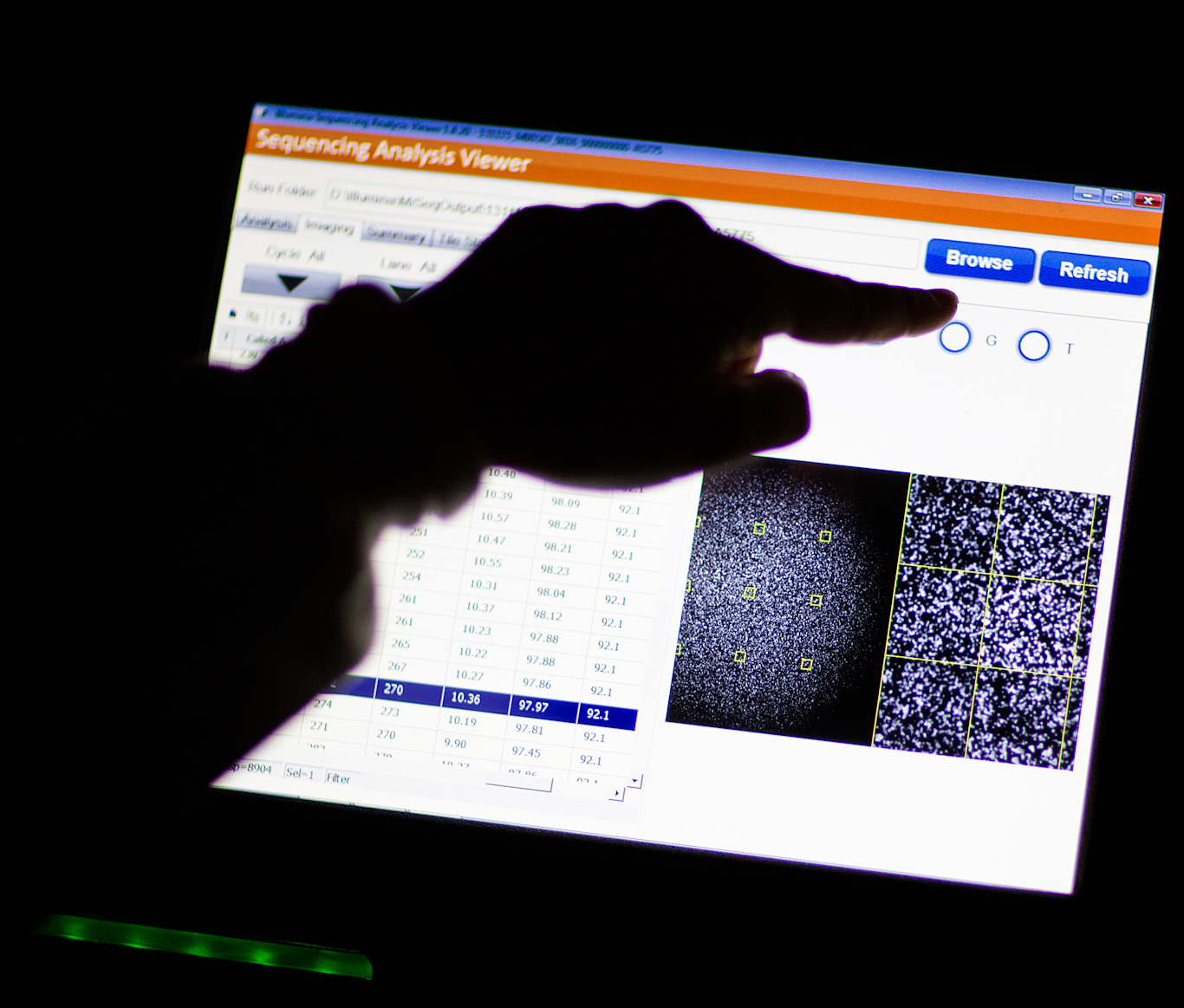

At the core of these efforts is the desire to create a DNA-based population screening agenda, which people like Perkins and Meyer are forcefully pushing forward. Perkins worked as the CMO at a company called Human Longevity, Inc., which “combines state-of-the-art DNA sequencing and expert analysis with machine learning, to help change medicine to a more data-driven science.”

Meyer developed a precursor to CommonPass in 2016, when he merged his mobile health services company, Voxiva, which implemented the “first nationwide digital disease surveillance systems in Peru and Rwanda” in partnership with the CDC, the National Institutes of Health (NIH), with Sense Health to form a health messaging service called Wellpass Meyer described as “an integrated platform… [that] helps overcome the challenges of deploying fragmented engagement and population health solutions.”

Dubious technology

The reliability of the DNA-based, algorithmically-deduced health diagnoses used for the CommonPass trial run must also be called into question given the history of the company furnishing the technology. Prenetics, Ltd is the Hong Kong-based, Alibaba-funded company that also performed the COVID-19 testing for the UK’s Premier League’s Project Restart, which used a similar health status app called Covi-Pass, covered by this author in June.

Prenetics’ COVID tests rely on DNA-based technology it acquired in 2018, when it purchased DNAFit; a company founded by South African businessman Avrom “Avi” Lasarow, who came on board after the merger as Prenetics’ Chief Executive Officer for Europe, Middle East and Africa. Lasarow, who also heads the Premier League’s coronavirus testing program, just settled a civil case against him in the U.S. last May for nearly $60,000 surrounding allegations of “deceptive health claims”.

“Lifestyle genetics pioneer” Lasarow has a long track record of settling out of court over such issues, including a lawsuit brought by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission in 2015, which accused Lasarow Healthcare Technologies Ltd., aka L Health Ltd., and two other defendants of making false or unsubstantiated claims regarding a “melanoma detection” app. As part of that settlement, Lasarow was “prohibited from making any misleading or unsubstantiated claims about the health benefits or efficacy of any product or service.”

Prenetics has been reportedly working on establishing a partnership with VSTE Enterprises, the same company that developed the V-Code technology that underpins Covi-Pass, since May. Nevertheless, such red flags pale in comparison to the individuals and organizations that are behind CommonPass, itself, who have plans for a much vaster digital enclosure based on DNA population screening technologies through initiatives like the The Commons Project, which aims to fundamentally transform medicine and impose new limits on our freedom of movement as the CommonPass rollout is slated to quickly expand to other routes across Asia, Africa, the Americas, Europe and the Middle East.

A common thread

Just as Bush’s Aviation and Transportation Security Act opened the doors for certain technology and security sectors to flourish in the wake of 9/11, this novel health-focused expansion of the national security state has bypassed all levers of democratic power to allow for the entrenchment of a far larger and more dangerous group of entities, within the health, technology and life sciences industries together with an increasingly more powerful clique of federal health agencies and officials, like Robert Kadlec, who are pushing for a full spectrum surveillance society.

Taking your shoes off at the airport and exposing your body to radiation has become routine now at every airport in the nation and most ‘temporary’ laws passed through emergency legislation remain on the books nearly two decades later. Precedent demands that we assume the same will occur with the majority of the new restrictions on our freedom of movement and quality of life currently being implemented throughout the country and the world.

Rolling back these draconian measures is not in any of their plans, as promised by the president of the U.S. Travel Association, Roger Dow, who confidently asserted after Wednesday’s successful CommonPass trail run, that the app will let us “navigate out of the crippling economic fallout of COVID-related travel restrictions and quarantine requirements,” adding that it will “pay further dividends for more seamless and convenient travel even once the pandemic has subsided.”

Feature photo | The CommonPass generated QR code is shown. Original image sourced from the Common Project

Raul Diego is a MintPress News Staff Writer, independent photojournalist, researcher, writer and documentary filmmaker.