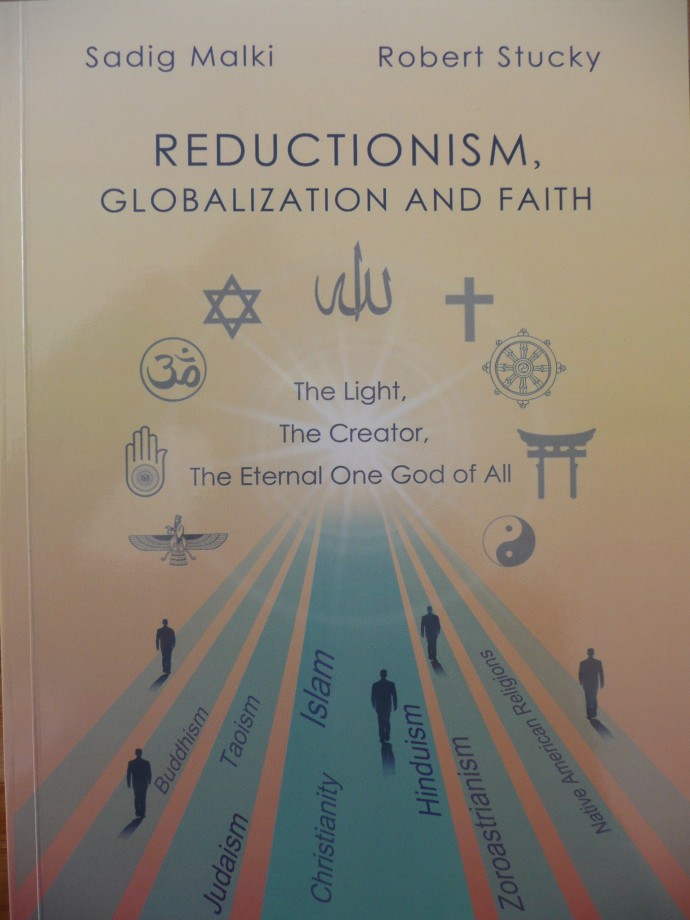

(BRUSSELS) — One is a tall American, a former Episcopal priest, who studied for years with a Hindu master of meditation, is loquacious, works as a medical interpreter and is the director of the Cultural Diversity and Competence Initiative in Baltimore, Md. The other is much smaller, an associate professor of political science at the University in Djeddah in Saudi Arabia, is a former diplomat and speaks in a soft, almost shy, voice. Together, they wrote “Reductionism, Globalization and Faith,” an essay about reconciling our religious preferences that was presented last week in Brussels.

What brought Robert Stucky and Sadig Malki, two men of so radically different backgrounds, together? In 2001, Sadig Malki explained, “I was in Baltimore because my daughter needed medical treatment. Robert’s parish was just across the street of the hospital and so, I started attending his services. One day, I arrived as usual and realized the services’ hours had changed.” Instead, there was a study of the Bible, and Malki decided to stay and attend. This is how a fascinating and stimulating dialogue started between the two men. “Sadig would provide a Muslim perspective on the Bible; and I would provide a Christian perspective on related material in the Muslim tradition. And we realized how much the two scriptures had in common,” says Stucky.

And then came 9/11. Malki and Stucky were alarmed by the abuse of scriptures to justify political violence “by all sides,” Stucky insists. “This, we believed, was a very selective reading of scriptures. And it was very worrisome that there was no liberal voice to speak against it. It was almost like a conspiracy of silence, no one to denounce the hypocrisy. Sadig and I believe the scriptures are a message of peace and so we decided to write an article. But it was not enough, we needed something more interactive. We then created the Faith in Diversity Institute to fight religious ignorance and intolerance through a non-competitive comparison of the world scriptures and the spiritual practices enshrined within them.”

At the time, the article went almost unnoticed. Nine more years were necessary to refine it and make it into an essay. The book, which gathers five different linguistic versions, is a call for harmony and peace in a pluralistic world. “Despite the astonishing degree of agreement to be found among the sacred scriptures of the world concerning the existence of a single, universal and conscious ground of being, the greatest obstacle to peace is the reductionism by which individuals and societies limit our understanding of that Source to our political, cultural and religious preferences,” Malki and Stucky write.

For a certain number of reasons, they explain, because we cannot grasp the enormity of the Divine as it is, because we need words to  speak about it and words are reductionist, humans have limited the concept of the Divine in a certain number of ways. They limit it to some particular historic event, like the birth of Jesus or the Hegira of Muhammad; they limit it to certain races or cultures, like Christianity has made Jesus a white man, a European, although he is a Middle-Easterner, hence probably darker than what we think; they also limit it to a single gender, but if God is infinite, God cannot have a gender; they limit it to a symbol, like the Cross or the Crescent. In other words, explains Stucky, “We reduce the absolute, the infinite, to a formula of our own choosing, which fits into our limited understanding. We then get so attached to that formula that we forget what it stands for and we are convinced that ‘my formula is better than yours.’ On a political level, this results in a bloody competition between the preferences chosen by each culture or society. And we end up with the oxymoron that all traditions say that there is only one God but in the end my God is always better than yours!”

speak about it and words are reductionist, humans have limited the concept of the Divine in a certain number of ways. They limit it to some particular historic event, like the birth of Jesus or the Hegira of Muhammad; they limit it to certain races or cultures, like Christianity has made Jesus a white man, a European, although he is a Middle-Easterner, hence probably darker than what we think; they also limit it to a single gender, but if God is infinite, God cannot have a gender; they limit it to a symbol, like the Cross or the Crescent. In other words, explains Stucky, “We reduce the absolute, the infinite, to a formula of our own choosing, which fits into our limited understanding. We then get so attached to that formula that we forget what it stands for and we are convinced that ‘my formula is better than yours.’ On a political level, this results in a bloody competition between the preferences chosen by each culture or society. And we end up with the oxymoron that all traditions say that there is only one God but in the end my God is always better than yours!”

Faith in the ultimate, Malki and Stucky believe, should not be historically or culturally bound but should be relevant to the history of humankind as a whole. The basic assumption here is that if the conscious, all-encompassing creative power is, in fact, the God of all, then that God cannot be tied to a given human category. It is necessarily beyond any time frame, physical understanding or intellectual categorization, beyond any given event in human history or human symbol. The two authors have hence taken as a point of departure the idea that all traditions share an awareness of some kind of overarching power that seems to permeate the universe to explore whether world religions can agree on some kind of defining criterion to uniformly recognize that power source. Such criterion can only be established by clearing all artificially limiting cultural biases.

The objective is to rule out ideas that contain or limit God within a particular human construct. Because God is one. And so, the concept of the Divine or Source or Consciousness must be generic and not tied to any time or cultural frame. “We are all the expression of a single Consciousness,” says Stucky. “And there are actually scientific reasons to believe we are all connected. Finding a common criterion would permit us to move toward a more universal understanding of our essential interconnectedness, which would be accepted and promoted by all the major religions of the world. That would certainly make us able to facilitate greater understanding and cooperation in human interaction across cultures.”

“Human beings everywhere have the same questions,” Malki intervenes. “Who I am, where do I come from? Where am I going? These are not culturally specific.” Most of the time, they look outward for answers; they look for well-being, for satisfaction in the outer world. In their spiritual practice, too, they concentrate on the outer forms, on rituals. “But you can cross yourself 10,000 times,” argues Stucky, “and it may not do anything to you! These practices may be meaningful or just external motions that have no uplifting emotions; it all depends on the awareness you bring upon that act. The locus of our experience is inside, not outside. Turning within us is nurturing and all the spiritual practices in these traditions are vehicles to turn us within. All traditions recognize that developing your awareness has a qualitative effect in your daily living. Meditation is one transcultural practice that showed up in all traditions in different forms.”

“In Islam, “Malki adds, “there is something that says “there is not much for you in prayer if you don’t do it with consciousness.’”

“What matters is not religion,” Stucky concludes. “What matters is that spiritual experience on a deeper level that we are all interconnected and so we can interact more constructively with each other; how you get there is your business. We need to pay attention to each others’ sensitivities; but most of all, we need to be self-aware about what pushes our buttons; if we are not self-aware, our awareness of others is necessary limited. So, you have to be able to step outside of yourself and outside of your ego; ego is the death of us all. All traditions make clear that you cannot access Enlightenment if you don’t transcend the ego. Practices are meant to help us do just that. Otherwise we merely reinforce our limitations.”

And, as Malki and Stuky write, “In a shrinking world and a volatile global community we can no longer afford to ignore our common bonds nor idolize our preferences at the expense of the common good.” Hence, their triple appeal: 1) We have to look how we introduce the concept of Divinity to our children and in our places of worship; 2) We have to open the doors of our worship places to non-members in an inclusive, not exclusive, way; and 3) We have to stand up against politicians who try to create the fear of the Other.

Stucky and Malki have very limited means, no real agenda on how to get their message across and don’t really know where to take it from there, although they are already speaking about a second book. What is clear, though, is that they are passionate about their message and eager to get it out to the world, a world that urgently needs it.