“The Disappearing Women”; “What is Philosophy’s Problem with Women?”; “Philosophy Has a Woman Problem!” These are some of the headlines of a smattering of recent articles seeking to examine the reality that women in the academic field of philosophy are sorely underrepresented.

According to a recent survey, in 2011 just 21.9 percent of the tenure-track faculty in 51 philosophy graduate programs were women. It’s also worth noting that the percentage of Black female professors was even smaller.

These stark and depressing statistics have led Jennifer Saul, a professor of philosophy at the University of Sheffield, to conclude, “Philosophy, the oldest of the humanities, is also the malest (and the whitest). While other areas of the humanities are at or near gender parity, philosophy is actually more overwhelmingly male than even mathematics.”

I have taught courses in philosophy for the Minnesota State University and Colleges system, a collection of community colleges, state universities and technical colleges, for the past seven years.

Female and male colleagues and I have discussed this trend for several years now, as articles published in journals such as the Chronicle of Higher Education have hinted and the growing gender gap in various humanities disciplines.

Regan Penaluna, an assistant professor of philosophy at St. John’s University in New York, speculated that “women are turned off by the canon of philosophy” adding that the discipline “is heavily weighted toward men and at times even hostile to women.”

However, in the years since the trend first become conspicuous, the gap only seems to be growing, or at least holding steady even as the topic ostensibly garners more attention.

“I’m a philosopher”

The New York Times published a series of essays last week on the topic of women in philosophy, written by various women philosophers, who seem as perplexed by the problem as the world at large.

As Sally Haslanger, a professor of philosophy and the former director of women’s and gender studies at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the president of the Eastern Division of the American Philosophical Association, wrote in one article that she often has difficulty telling people what she does for a living.

When asked that question, she said her reply — “I’m a philosopher” — has prompted laughter.

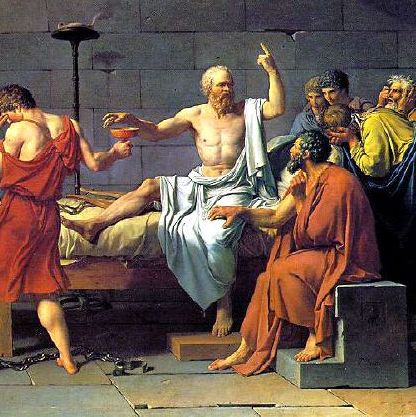

“Once when I queried why the laughter, the response was, ‘I think of philosophers as old men with beards, and you’re definitely not that! You’re too young and attractive to be a philosopher.’ I’m sure he intended this as a compliment. But I stopped giving the answer ‘I’m a philosopher,’” she wrote. “Although most philosophers these days are not old men with beards, most professional philosophers are men; in fact, white men. It is a surprise to almost everyone that the percentage of women earning philosophy doctorates is less than in most of the physical sciences.”

While women have made strides in the field of philosophy, the discipline had a lower percentage of women doctorates than even notorious male-heavy disciplines like math, chemistry and economics.

When it comes to the issue of people of color within the field of philosophy, the situation is even more dire, with Haslanger calling the statistics “appalling,” particularly for women of color. In 2003, of 13,000 full-time philosophy instructors in the United States, there were a recorded 16.6 percent full-time women philosophy instructors. Of these there were no women of color represented. “Apparently there was insufficient data for any racial group of women other than white women to report. The APA Committee on the Status of Black Philosophers and the Society of Young Black Philosophers reports that currently in the United States there are 156 blacks in philosophy, including doctoral students and philosophy Ph.D.s in academic positions; this includes a total of 55 black women, 31 of whom hold tenured or tenure-track positions,” Haslanger said.

Philosophy: a tool for defending harassment?

Some have postulated that factors such as sexual harassment may be to blame for the low numbers of women entering the field. At a recent department meeting I attended, one colleague shared that a graduate school classmate of hers had dropped out of the program after dealing with sexual harassment. Unfortunately, I too have seen friends struggle with this problem while a graduate student. Is it a problem unique to the field of philosophy? I doubt that. My sense is that it as a problem widespread throughout academia and pervasive in American society at large.

Nevertheless, the story of Colin McGinn, touted as “a star philosopher at the University of Miami” by the New York Times, who stepped down earlier this year from his tenured post after allegations of sexual harassment were brought by a graduate student, made headlines across the world earlier this year and inspired further investigation into the reasons behind why less women seem to be attracted to the field.

McGinn used “the cryptic language of analytic philosophy in attempts to defend himself” in posts on his blog, reported the Times. He claimed the student wasn’t bright enough to realize the harmless nature of his jokes, and this argument “seems to have backfired,” the Times went on to say, as the posts drew concern for the student who reported McGinn from other academics in the field. In July, over 100 such professionals signed a letter urging the University of Miami to protect the student “from negative public assessments of her work or character by or on behalf of Dr. McGinn.”

A world of small numbers

So what does the future look like for women and people of color in the field of philosophy? While the immediate situation is problematic, it’s heartening that the problem is being discussed at all, and that universities and academics can begin devising strategies to combat this problem.

However, the reason for the low numbers of women in the field remains to be concretely determined. It is especially troubling considering it’s been almost a half-century since the first wave of feminism inspired women to see themselves as equals with men, and opened doors for their intellectual and personal development in every area of society.

“With these numbers, you don’t need sexual harassment or racial harassment to prevent women and minorities from succeeding, for alienation, loneliness, implicit bias, stereotype threat, microaggression, and outright discrimination will do the job,” concludes Haslanger. “But in a world of such small numbers, harassment and bullying is easy.”