WASHINGTON — The U.S. military and the Obama administration have come under increased pressure from the courts, lawyers, activists and the media in recent weeks to relax strict classification rules around videotapes showing what advocates allege is mistreatment of detainees at the detention center at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba.

The push for legal access to videotaped evidence from Guantánamo has gone on for years, strengthened in part by accusations that the CIA has destroyed tapes related to interrogations in “black sites” across the globe. More recently, however, this movement has coalesced — and started seeing some success — around allegations of improper treatment surrounding the force-feedings that hunger-striking detainees, frustrated over their indefinite detention, have been subjected to since early last year.

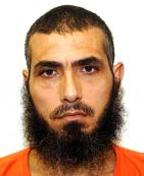

This effort achieved a major legal victory in late May, around the case of Abu Wa’el Dhiab, a Syrian citizen who has alleged that he was injured and that his rights were violated as part of force-feedings that took place over the past two years. In what was widely seen as a landmark decision, a district court judge in Washington halted Dhiab’s force-feeding.

Although the judge, Gladys Kessler, later allowed these feedings to resume over fears for Dhiab’s life, she also mandated that the government hand over nearly three-dozen videotapes said to depict Dhiab’s treatment by Guantánamo personnel. On Thursday, the government was slated to give up another tranche of these tapes to Dhiab’s legal team.

The videos reportedly include depictions of both the force-feedings and the procedures under which Dhiab was forcibly removed from his cell. The order has allowed lawyers, for the first time, to formally gain access to taped evidence from Guantánamo.

New efforts are now underway to build on this success, both in terms of forcing the disclosure of tapes of other detainees’ treatment and in trying to get some of this material released into the public sphere. On Wednesday, lawyers asked the courts to allow the tapes to be shared with a broader network of security-cleared attorneys.

The effort toward public disclosure, meanwhile, was strengthened in mid-June, when 16 major media houses, including The Associated Press, The New York Times and National Public Radio, asked Judge Kessler to make public more than a dozen of the Dhiab videos that have been entered as evidence in the ongoing trial.

Although filed with the court, the videos remain sealed, classified as secret information pertaining to national security. (A Pentagon spokesperson was unable to comment for this story by deadline.)

“Although the Government has classified the videotapes, it is no secret that force-feeding is being used at Guantanamo; nor is there any secret regarding how it is used,” the lawyers for the news organizations argue.

“To the contrary, the public access right should be fully enforced because the videotapes are the most direct and informative evidence of Government conduct that [Dhiab] alleges to be unlawful … The public is entitled to view this evidence to satisfy itself of the fairness of the outcome of this proceeding and to exercise democratic oversight of its Government.”

Following an extension, the government is scheduled to give its response to these allegations by July 18.

Dhiab’s precedent

While Dhiab’s lawyers wanted access to the videotapes as part of the detainee’s lawsuit around force-feeding, they too are embracing the broader push to get the tape released into the public domain.

“Almost every major news outlet in the U.S. has intervened in the case of my client, asking Judge Kessler to make the tapes of his forced cell extractions and force-feedings public in the national interest,” Cori Crider, an attorney for Dhiab with Reprieve, a British legal advocacy group, told MintPress News. “The American people have a right to know what is being done in their name.”

Crider was one of just a few lawyers who were recently allowed to go to a Pentagon-operated facility in Virginia and view all of the footage released thus far, said to have been filmed between April 2013 and February of this year. She said in a statement that she was barred from discussing the contents of the tapes but noted that she had “had trouble sleeping after viewing them.”

She reminded MintPress that President Obama had promised to run the most transparent U.S. administration in history.

“I believe if he watched the tapes of how my client is being treated,” she said, “he would bring some of that transparency to Guantánamo and stop this abuse of cleared detainees.”

Dhiab was arrested in Pakistan in 2002 and sent to Guantánamo. Yet, as Crider notes, the Obama administration cleared him for transfer in 2009. Of the 149 men who remain detained at Guantánamo, more than half have been cleared for transfer.

While Dhiab’s case has since languished, it was reinvigorated in May when Uruguayan President Jose Mujica reiterated an offer to take in Dhiab and five other Guantánamo detainees who have long been cleared for transfer. Last week, lawyers for these six men sent a letter to administration officials to inquire about the status of these plans. As far back as February, they noted, they had been told that such transfers would take place in “a matter of weeks, not months.”

Yet the Uruguay proposal has since been thrown into question by the political brouhaha over the agreement made between the Obama administration and the Afghan Taliban over the captured U.S. soldier Bowe Bergdahl. That accord led to the transfer of five Taliban members into Qatari custody, a price that some Republicans have said was too great to pay for a single U.S. service member with a disputed record.

The U.S House of Representatives passed a major defense spending bill on June 20 that includes new restrictions to transferring Guantánamo detainees. The White House has expressed its “strong” opposition to the provision, but has not gone so far as to say it would veto the bill. Uruguay, meanwhile, will hold national elections in October, and it’s unclear what will happen to President Mujica’s offer thereafter.

Even as his transfer remains on hold, however, Dhiab’s legal victory around access to videotaped evidence is already being seized upon as a precedent. Within days of Judge Kessler’s original ruling, another Guantánamo detainee, Mohammad Ahmad Ghulam Rabbani, a Pakistani who has been held for over a decade without charge, filedsuit to try to compel the military to release tapes of his treatment.

Rabbani is also being represented by Reprieve, which has stated that the tapes depict treatment that included “gratuitous brutality.”

“Mr. Rabbani has repeatedly reported disturbing abuse at the hands of the Guantánamo authorities, as have so many of his fellow hunger-strikers. Yet the prison denies it, and has flatly refused even the smallest requests to make the force-feeding process more humane,” Reprieve’s Crider said.

“These videos can only help us get to the truth. The court must be allowed to see exactly what is going on daily at Guantánamo Bay.”

Power of the visual

In separate legal proceedings, last week lawyers urged a circuit court in New York to require the public release of videotapes depicting the treatment of another Guantánamo prisoner, Mohammed al Qahtani. His advocates say he is the only prisoner that the U.S. government has acknowledged torturing, activities said to have taken place during 2002 and 2003.

According to a military interrogation log, Qahtani appears to have undergone a range of harsh interrogation and abusive treatment over the course of 48 days during that period. He is said to have come close to dying at least twice.

Now, Qahtani’s lawyers say videotapes exist from the period just prior to his abuse, during which he was kept for long periods in solitary confinement, as well of subsequent debriefings. According to the legal brief filed by his attorneys under the Freedom of Information Act, the existence of these tapes was acknowledged by the government in 2009.

The government has suggested that the tapes should remain classified over concerns that their content could lead to or strengthen anger against the United States, according to Shayana Kadidal, an attorney with the Guantánamo Global Justice Initiative at the Center for Constitutional Rights, a New York legal advocacy group.

“The government has claimed that [the tapes] don’t show any abusive treatment, but our feeling is that the public ought to be able to judge on their own,” Kadidal told MintPress. “If the tapes don’t show the abuse claimed, then it’s hard to understand how this would enflame people in the Muslim world. But if they do show abuse, that’s a clear problem.”

Kadidal notes that the CIA has been accused of destroying nearly 100 tapes of interrogations at agency “black sites” around the world. In addition to an agency covering its own trail, the allegations also underscore how the government has long been cognizant — and fearful — of the impact that video can have on public opinion. Kadidal points, for instance, to a longstanding debate over whether televising executions would quickly sour the public on death penalty-related policy.

“Look at all of these novel practices since 9/11 — sleep deprivation, solitary confinement — that have been sold to the public as acceptable because they don’t leave marks, because they’re ‘touchless,’” he said.

“Force-feedings are kind of the same thing, but of course the details actually include being strapped in, with a tube inserted for each meal, and fed so much that you defecate. On paper those things don’t seem terribly bad, but videotapes of them … have the potential to completely change the public debate.”